Eric Gill: Difference between revisions

meta>Mervyn Undid revision 252573653 by 194.80.225.2 (talk) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (512 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{for|the footballer|Eric Gill (footballer)}}{{Delete}}{{short description|English sculptor, typeface designer, and printmaker}} | |||

{{Use British English|date=August 2014}} | |||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2020}} | |||

{{Infobox artist | |||

|image= Eric Gill - self portrait.jpg | |||

|caption= Self-portrait | |||

|name=Eric Gill | |||

|birth_name=Arthur Eric Rowton Gill | |||

|birth_date= {{birth date|df=yes|1882|2|22}} | |||

|birth_place=[[Brighton]], Sussex, England | |||

|death_date= {{death date and age|df=yes|1940|11|17|1882|2|22}} | |||

|death_place=[[Middlesex]], England | |||

|education= {{ubl|Chichester Technical and Art School|[[Westminster Technical Institute]]|[[Central School of Art and Design|Central School of Arts and Crafts]]}} | |||

|known_for = Sculpture, [[typography]] | |||

|movement = [[Arts and Crafts movement]] | |||

}} | |||

'''Arthur Eric Rowton Gill''' {{Post-nominals|country=GBR|ARA}} ({{IPAc-en|ɡ|ɪ|l}};<ref>{{cite book|last1=Olausson|first1=Lena|last2=Sangster|first2=Catherine|title=Oxford BBC Guide to Pronunciation|year=2006|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, England|isbn=978-0-19-280710-6|page=150}}</ref> 22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, [[Typography|typeface designer]], and [[Printmaking|printmaker]], who was associated with the [[Arts and Crafts movement]]. His religious views and subject matter contrast with his [[Human sexual behavior|sexual behaviour]], including his [[erotic art]], and (as mentioned in his own diaries) his extramarital affairs and sexual abuse of his daughters, sisters, and dog. | |||

Gill was named [[Royal Designers for Industry|Royal Designer for Industry]], the highest British award for designers, by the [[Royal Society of Arts]]. He also became a founder-member of the newly established Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry. | |||

Gill was | |||

==Early life and studies== | |||

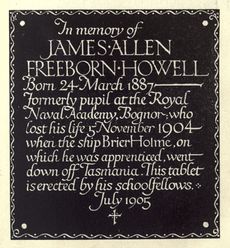

[[File:Gill bronze.jpg|thumb|upright|A rubbing of a memorial bronze created by Eric and Max Gill in 1905]] | |||

Gill was born in 1882 in Hamilton Road, Brighton, the second of the 13 children of (Cicely) Rose King (''d''. 1929), formerly a professional singer of light opera under the name Rose le Roi, and Rev. Arthur Tidman Gill, minister of the [[Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion]], who had recently left the [[Congregational church]], after doctrinal disagreements. He was the elder brother of graphic artist [[MacDonald Gill|MacDonald "Max" Gill]] (1884–1947).<ref>{{Citation|title=The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography|date=2004-09-23|url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/33403|work=The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography|pages=ref:odnb/33403|editor-last=Matthew|editor-first=H. C. G.|publisher=Oxford University Press|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/33403|access-date=2019-12-12|editor2-last=Harrison|editor2-first=B.}}</ref> In 1897 the family moved to [[Chichester]]. | |||

Gill studied at Chichester Technical and Art School, and in 1900 moved to London to train as an architect with the practice of [[W. D. Caröe]], specialists in ecclesiastical architecture. | |||

Frustrated with his training, he took evening classes in stonemasonry at the [[Westminster Technical Institute]] and in [[calligraphy]] at the [[Central School of Art and Design|Central School of Arts and Crafts]], where [[Edward Johnston]], creator of the [[London Underground]] [[Johnston (typeface)|typeface]], became a strong influence. In 1903 he gave up his architectural training to become a calligrapher, letter-cutter and monumental mason.<ref name="WatSCA">{{cite web|title=Eric Gill archival and book collection|url=https://uwaterloo.ca/library/special-collections-archives/collections/gill-eric|website=University of Waterloo Library|publisher=Special Collections & Archives|accessdate=18 May 2016}}</ref><ref name="Font Designer – Eric Gill" /><ref name="WACML" /> | |||

Gill | Gill's first apprentice in 1906 was [[Joseph Cribb]] (1892–1967) a sculptor and letter carver, who came to Ditchling with Gill in 1907.<ref>{{NHLE|num=1438295|desc=Ditchling War Memorial|accessdate=11 January 2020}}</ref> [[Hilary Stratton]], was an apprentice sculptor between 1919 and 1921.<ref>Sussex Life article by Vida Herbison, Sussex sculptor and stonemason, undated article c 1975</ref> | ||

==Career== | |||

===Sculpture=== | |||

Working from [[Ditchling]] in [[Sussex]], where he lived with his wife, in 1910 Gill began direct carving of stone figures. These included ''Madonna and Child'' (1910), which English painter and art critic [[Roger Fry]] described in 1911 as a depiction of "pathetic animalism", and ''[[Ecstasy (Gill sculpture)|Ecstasy]]'' (1911). Such semi-abstract sculptures showed Gill's appreciation of medieval ecclesiastical statuary, Egyptian, Greek and Indian sculpture, as well as the Post-Impressionism of Cézanne, van Gogh and Gauguin.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/eric-gill-1168|title=Eric Gill – Tate|work=Tate|accessdate=13 February 2015}}</ref> | |||

== | His first public success was ''Mother and Child'' (1912). A self-described "disciple" of the [[Ceylonese]] philosopher and art historian [[Ananda Coomaraswamy]], Gill was fascinated during this period by [[Architecture of India|Indian temple sculpture]].<ref>[http://vimeo.com/arrowsmith/cosmopolitanism-and-modernism Video of a Lecture at London University detailing Gill's interest in Indian Sculpture], ''[[London University School of Advanced Study]]'', March 2012.</ref> Along with his friend and collaborator [[Jacob Epstein]], Gill planned the construction in the Sussex countryside of a colossal, hand-carved monument in imitation of the large-scale [[Jainism|Jain]] structures at [[Gwalior Fort]] in Madhya Pradesh, to which he had been introduced by [[William Rothenstein]].<ref>{{cite book|author= Rupert Richard Arrowsmith| date=2010 | title=Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African, and Pacific Art and the London Avant-Garde | publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] | pages=74–103 | isbn=978-0-19-959369-9 }}</ref> | ||

[[Image: | |||

In 1914, Gill produced sculptures for the stations of the cross in [[Westminster Cathedral]].<ref name=FRoher>{{cite web |author=Finlo Roher|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/6979731.stm |title=Can the art of a paedophile be celebrated ?|date=5 September 2007|accessdate=10 August 2008|work=BBC News}}</ref> In the same year, he met the typographer [[Stanley Morison]]. After the war, together with [[Hilary Pepler]] and [[Desmond Chute]], Gill founded [[The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic]] at Ditchling. There his pupils included [[David Jones (poet)|David Jones]], who soon began a relationship with Gill's daughter, Petra. | |||

Gill designed several war memorials after the First World War, including the Grade II* listed [[Trumpington War Memorial]]. Commissioned{{when|date=July 2015}} to produce a [[war memorial]] for the [[University of Leeds]], Gill produced a frieze depicting Jesus driving the money-changers from the temple, showing contemporary [[Leeds]] merchants as the money-changers. Gill contended that the "money men" were a key cause of the war. This is at the [[Michael Ernest Sadler|Michael Sadler]] Building at the University. | |||

In 1924, Gill moved to [[Capel-y-ffin]] in [[Powys]], [[Wales]], where he established a new workshop, to be followed by Jones and other disciples. In 1928, he set up a printing press and lettering workshop in [[Speen, Buckinghamshire]]. He took on a number of apprentices, including [[David Kindersley]], who in turn became a successful sculptor and engraver, and his nephew, [[John Skelton (sculptor)|John Skelton]], noted as an important letterer and sculptor. Other apprentices included Laurie Cribb, [[Donald Potter]] and [[Walter Ritchie]].<ref>C.f. Donald Potter, ''My Time with Eric Gill: A Memoir'', Gamecock Press, 1980, {{ISBN|0-9506205-1-3}}.</ref> Others in the household included Gill's two sons-in-law, Petra's husband Denis Tegetmeier and Joanna's husband Rene Hague. | |||

In 1928–29, Gill carved three of eight relief sculptures on the theme of winds for [[Charles Holden]]'s headquarters for the [[Underground Electric Railways Company of London|London Electric Railway]] (now [[Transport for London]]) at [[55 Broadway]], [[St James's]]. He carved a statue of the ''[[Virgin and Child]]'' for the west door of the chapel at [[Marlborough College]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.marlboroughcollege.org/about-us/facilities/chapel/art-architecture/|title=Art & Architecture|date=20 July 2011|work=marlboroughcollege.org|accessdate=13 February 2015}}</ref> | |||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" mode="nolines"> | |||

File:Eric-Gill---Nude-woman-reclining-on-a-leopard-skin-(1928).png|''Nude woman naked reclining on a leopard skin'', a [[graphite]] drawing by Gill (1928). | |||

File:55Broadway EricGill NorthWind.jpg|''North Wind'', [[55 Broadway]]. | |||

File:Ariel between Wisdom and Gaiety.jpg|''Ariel Between Wisdom and Gaiety'', [[Broadcasting House]], 1932. | |||

File:Lapworth Eric Gill bas relief 2015.jpg|[[Bas-relief]] in [[Lapworth]] parish church, 1928. | |||

File:East Jerusalem, the Rockefeller Museum Rockefeller Museum P1190104.JPG|Relief representing [[Israelite]] culture, one of ten bas-reliefs by Gill in the inner courtyard at the [[Rockefeller Museum]], Jerusalem, 1934. | |||

</gallery> | |||

In 1932, Gill produced a group of sculptures, ''Prospero and Ariel'',<ref>[[:File:Prospero and Ariel-2.jpg|Illustration]].</ref> and others for the BBC's [[Broadcasting House]] in London. | |||

In 1934, Gill visited Jerusalem where he worked at the [[Palestine Archaeological Museum]] (now the [[Rockefeller Museum]]).<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.imj.org.il/rockefeller/eng/Gill.html | title=Eric Gill, 1882–1940 | publisher=[[Israel Museum]] | work=East Meets West: The Story of the Rockefeller Museum | accessdate=31 January 2016 }}</ref> He carved a stone [[bas-relief]] of the meeting of Asia and Africa above the front entrance together with ten stone reliefs illustrating different cultures and a [[gargoyle]] fountain in the inner courtyard. He also carved stone signage throughout the museum in English, Hebrew and Arabic. | |||

[[File:St. Peter's Catholic Church Gorleston.jpg|thumb|right|St Peter the Apostle in Gorleston, Norfolk (1938–9), Gill's only completed building]] | |||

Gill was commissioned to produce a sequence of seven bas-relief panels for the façade of The People's Palace, now the Great Hall of [[Queen Mary University of London]], which opened in 1936. In 1937, he designed the background of the first [[George VI of the United Kingdom|George VI]] [[definitive stamp]] series for the post office.<ref>Peter Worsfold, ''Great Britain King George VI Low Value Definitive Stamps'', The Great Britain Philatelic Society, 2001, {{ISBN|0-907630-17-0}}. The effigy of George VI was drawn by [[Edmund Dulac]], who had a debate with Gill in newspapers about stamp designing after the [[Edward VIII postage stamps]] late-1936, quoted in Colin White, ''Edmund Dulac'', Studio Vista, 1977, p. 172.</ref><ref name=KRPress>{{cite web |url=http://www.katranpress.com/stamps_gill_1_1.html |title=Eric Gill Postage Stamps by Type Designer|accessdate=31 January 2018|work=The Offices of Kat Ran Press}}</ref> In 1938 Gill produced ''The Creation of Adam'', three bas-reliefs in stone for the [[Palace of Nations, Geneva|Palace of Nations]], the [[League of Nations]] building in [[Geneva]], Switzerland.<ref name=FRoher/> During this period he was made a [[Royal Designers for Industry|Royal Designer for Industry]], the highest British award for designers, by the [[Royal Society of Arts]] and became a founder-member of the Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry when it was established in 1938. In April 1937, Gill was elected an Associate member of the [[Royal Academy]].<ref name=RAcademy>{{cite web |url=http://www.racollection.org.uk/ixbin/indexplus?_IXACTION_=file&_IXFILE_=templates/full/person.html&_IXTRAIL_=Academicians&person=5686 |title=Royal Academy of Arts collections, Eric Gill, A.R.A|accessdate=31 January 2018|work=Royal Academy of Arts}}</ref> | |||

Gill's only complete work of architecture was St Peter the Apostle Roman Catholic Church in [[Gorleston-on-Sea]], built in 1938–39. | |||

===Midland Hotel, Morecambe=== | |||

{{Main|Eric Gill works at the Midland Hotel, Morecambe}} | |||

[[Image:Eric Gill seahorse-Midland Hotel Morecombe.JPG|upright|thumb|One of Eric Gill's two seahorses above the entrance to the [[Eric Gill works at the Midland Hotel, Morecambe|Midland Hotel, Morecambe]]]] | |||

The [[Art Deco]] [[Midland Hotel, Morecambe|Midland Hotel]] was built in 1932–33 by the [[London Midland & Scottish Railway]] to the design of [[Oliver Hill (architect)|Oliver Hill]] and included works by Gill, [[Marion Dorn]] and [[Eric Ravilious]]. | |||

For the project, Gill produced: | |||

* two seahorses, modelled as Morecambe shrimps, for the outside entrance | |||

* a round plaster [[relief]] on the ceiling of the circular staircase inside the hotel | |||

* a decorative wall map of the north west of England | |||

* a large stone relief of [[Odysseus]] being welcomed from the sea by [[Nausicaa]]. | |||

===Typefaces and inscriptions=== | |||

One of Gill's first independent lettering projects was creating an alphabet for [[W.H. Smith]]'s sign painters. In 1925, he designed the [[Perpetua (typeface)|Perpetua]] typeface, with the uppercase based upon monumental Roman inscriptions, for Morison, who was working for the [[Monotype Corporation]]. An in-situ example of Gill's design and personal cutting in the style of Perpetua can be found in the nave of the church in [[Poling, West Sussex]], on a wall plaque commemorating the life of [[Sir Harry Johnston]]. | |||

He designed the [[Gill Sans]] typeface in 1927–30, based on the sans-serif lettering originally designed for the [[London Underground]]. (Gill had collaborated with [[Edward Johnston]] in the early design of the Underground typeface, but dropped out of the project before it was completed.) In the period 1930–31, Gill designed the typeface [[Joanna (typeface)|Joanna]] which he used to hand-set his book, ''[[An Essay on Typography]]''. | |||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" mode="nolines"> | |||

File:GillFaces.png|Specimens of typefaces by Eric Gill | |||

File:Golden Cockerel Press typeface.jpg|Gill's type for the [[Golden Cockerel Press]] | |||

File:Sir Harry Johnston memorial plaque.JPG|Sir [[Harry Johnston]] memorial plaque | |||

File:Lowestoft Central sign straightened.jpg|[[British Railways]] sign at [[Lowestoft railway station]] in Gill Sans | |||

</gallery> | |||

[[File:Eric_Gill_-_Alphabets_and_Numerals_(1909)_(V%26A).jpg|thumb|Alphabets and Numerals (1909).<br>Gill carved these for a book, ''"Manuscript and Inscription Letters for Schools and Classes and for the Use of Craftsmen"'', compiled by his former teacher, Edward Johnston. He later gave them to the Victoria and Albert Museum so they could be used by students at the Royal College of Art.]] | |||

Eric Gill's types include: | Eric Gill's types include: | ||

* | * [[Gill Sans]], 1927–30; many variants followed | ||

* | * [[Perpetua (typeface)|Perpetua]] (design started c. 1925, first shown around 1929, commercial release 1932) | ||

* | * Perpetua Greek (1929)<ref>{{cite book |author= Robert Harling| title = The Letter Forms and Type Designs of Eric Gill | publisher = Eva Svensson and David R. Godine| location = Boston, MA| year = 1978 | isbn = 0-87923-200-5}}</ref> | ||

* Golden Cockerel Press Type (for the [[Golden Cockerel Press]]; 1929)<ref name=Fonts>{{cite web |url=http://www.identifont.com/show?12W |title=Eric Gill (1882-1940), Fonts designed by Eric Gill|accessdate=31 January 2018|work=Identifont}}</ref> Designed bolder than some of Gill's other typefaces to provide a complement to wood engravings.<ref name="Eric Gill and the Cockerel Press Upper & Lower Case">{{cite web|last1=Mosley|first1=James|author-link=James Mosley|title=Eric Gill and the Cockerel Press|url=http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/GillCockerel.htm|website=Upper & Lower Case|publisher=International Typeface Corporation|accessdate=7 October 2016|url-status=bot: unknown|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120729035625/http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/GillCockerel.htm|archivedate=29 July 2012}}</ref><ref name="The Digital Development of ITC Golden Cockerel">{{cite web|last1=Brignall|first1=Colin|title=The Digital Development of ITC Golden Cockerel|url=http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/GoldenCockerelDev.htm|publisher=[[International Typeface Corporation]]|accessdate=8 February 2017|url-status=bot: unknown|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120614052810/http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/GoldenCockerelDev.htm|archivedate=14 June 2012}}</ref><ref name="The Golden Cockerel Press, Private Presses and Private Types">{{cite web|last1=Carter|first1=Sebastian|author-link=Sebastian Carter|title=The Golden Cockerel Press, Private Presses and Private Types|url=http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/PrivatePresses.htm|publisher=[[International Typeface Corporation]]|accessdate=8 February 2017|url-status=bot: unknown|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120521174438/http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/PrivatePresses.htm|archivedate=21 May 2012}}</ref><ref name="Robert Gibbings and the quest for types suitable for illustrated books">{{cite web|last1=Dreyfus|first1=John|author-link=John Dreyfus|title=Robert Gibbings and the quest for types suitable for illustrated books|url=http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/RobertGibbings.htm|publisher=[[International Typeface Corporation]]|accessdate=8 February 2017|url-status=bot: unknown|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120521182336/http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/RobertGibbings.htm|archivedate=21 May 2012}}</ref><ref name="A Publisher's Story">{{cite web|last1=Yoseloff|first1=Thomas|title=A Publisher's Story|url=http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/PubStory.htm|publisher=[[International Typeface Corporation]]|accessdate=8 February 2017|url-status=bot: unknown|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120520175854/http://www.itcfonts.com/Ulc/OtherArticles/PubStory.htm|archivedate=20 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

* | * [[Solus (typeface)|Solus]] (1929)<ref name="The Non Solus Story">{{cite web|last1=Bates|first1=Keith|title=The Non Solus Story|url=http://www.k-type.com/non-solus-story/|publisher=K-Type|accessdate=21 July 2015}}</ref><ref name=Fonts/> | ||

* | * [[Joanna (typeface)|Joanna]] (based on work by Granjon; 1930–31, not commercially available until 1958) | ||

* | * Aries (1932)<ref name=Fonts/> | ||

* | * Floriated Capitals (1932)<ref name=Fonts/> | ||

* | * Bunyan (1934) | ||

* | * Pilgrim (recut version of Bunyan; 1953)<ref name=Fonts/> | ||

* Jubilee (also known as Cunard; 1934)<ref name=Fonts/> | |||

These dates are somewhat debatable, since a lengthy period could pass between Gill creating a design and it being finalised by the Monotype drawing office team (who would work out many details such as spacing) and cut into metal.<ref name="Gill Sans after Gill" /><ref>{{cite web|last1=Rhatigan|first1=Dan|title=Time and Times again| url=http://ultrasparky.org/archives/2011/09/time_and_times_.html|publisher=Monotype|accessdate=28 July 2015}}</ref> In addition, some designs such as Joanna were released to fine printing use long before they became widely available from Monotype. | |||

The family Gill Facia was created by [[Colin Banks]] as an emulation of Gill's stone carving designs, with separate styles for smaller and larger text.<ref name="Gill Facia MT Fontshop">{{cite web|last1=Banks|first1=Colin|title=Gill Facia MT|url=https://www.fontshop.com/superfamilies/gill-facia|website=Fontshop|publisher=Monotype|accessdate=30 August 2015}}</ref> | |||

One of the most widely used British typefaces, Gill Sans, was used in the classic design system of [[Penguin Books]] and by the [[London and North Eastern Railway]] and later [[British Railways]], with many additional styles created by Monotype both during and after Gill's lifetime.<ref name="Gill Sans after Gill">{{cite web|last1=Rhatigan|first1=Dan|title=Gill Sans after Gill|url=http://image.linotype.com/files/pdf/GillSansArticle.pdf|publisher=Monotype|accessdate=11 September 2015}}</ref> In the 1990s, the BBC adopted Gill Sans for its [[Wordmark (graphic identity)|wordmark]] and many of its on-screen television graphics. | |||

== | ====Arabic==== | ||

Gill was commissioned to develop a typeface with the number of allographs limited to what could be used on Monotype or Linotype machines. The typeface was loosely based on the Arabic [[Naskh (script)|Naskh]] style but was considered unacceptably far from the norms of Arabic script. It was rejected and never cut into type.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Blair|first1=S.S|title=Islamic Calligraphy|page=606, Fig. 13.7}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Graalfs|first1=Gregory|title=Gill Sands|journal=Print|date=1998}}</ref><ref name="Eric Gill Monotype Recorder 1958">{{cite journal|title=Eric Gill|journal=Monotype Recorder|date=1958|volume=41|issue=3|url=http://www.metaltype.co.uk/downloads/mr/mr_41_3.pdf|accessdate=16 September 2015}}</ref> | |||

===Published works=== | |||

[[File:Gill woodcut Hammersmith.png|thumb|An Eric Gill woodcut showing [[Hammersmith]], illustrating the book ''The Devil's devices, or, Control versus Service'' by [[Hilary Douglas Clark Pepler|Hilary Pepler]], 1915]] | |||

Gill published numerous essays on the relationship between art and religion, and a number of erotic engravings.<ref>Christopher Skelton (ed.), ''Eric Gill, The Engravings'', Herbert Press, 1990, {{ISBN|1-871569-15-X}}.</ref> | |||

*''A Holy Tradition of Working: An Anthology of Writings'', Golgonooza Press | |||

*''Clothes: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women'', 1931 | Some of Gill's published writings include: | ||

*''An Essay on Typography'', 1931 | *''A Holy Tradition of Working: An Anthology of Writings''<ref>Gill, Eric. (1983). ''A Holy Tradition of Working: An Anthology of Writings'' Golgonooza Press. {{ISBN|0-903880-30-X}}.</ref> | ||

*''Clothes: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women''<ref>Cape, Jonathan. (1931). Jonathan Cape. Gill contributed: ''Clothes: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women''</ref> | |||

*''[[An Essay on Typography]]''<ref>Gill, Eric. (1931). ''An Essay on Typography'' {{ISBN|0-87923-762-7}}, {{ISBN|0-87923-950-6}} (reprints).</ref> | |||

*''Christianity and Art'', 1927 | *''Christianity and Art'', 1927 | ||

*''Art'', 1934 | *''Art'', 1934 | ||

*''Work and Property'', 1937 | *''Work and Property'', 1937<ref>Gill, Eric. (1937). ''Trousers & The Most Precious Ornament.'' London: Faber and Faber. oclc 5034115</ref> | ||

*''Work and Culture'', 1938 | *''Work and Culture'', 1938 | ||

*''Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus'' | *''Twenty-five nudes'', 1938<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/twentyfivenudes00gill|title=Twenty-Five Nudes|last=Gill|first=Eric|date=1951|publisher=J M Dent & Sons|access-date=2018-08-06}}</ref> | ||

*''Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus''<ref>Jonathan Cape, 1940 (published posthumously) ''Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus.'' {{ISBN|1-870495-13-6}}</ref> | |||

*''Notes on Postage Stamps''<ref>Gill, Eric. (2011). ''Notes on Postage Stamps'' Kat Ran Press, 2011. {{ISBN|0-9794342-1-1}}.</ref> | |||

*''Christianity and the Machine Age'', 1940.<ref>In the series ''Christian Newsletter Books'', The Sheldon Press.</ref> | |||

*''[https://stjamesparkpress.com On the Birmingham School of Art, 1940]'' | |||

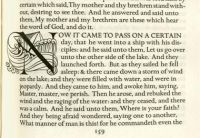

Gill also provided woodcuts and illustrations for a range of other books. | |||

==Political views== | |||

As a young man, Gill was a member of the [[Fabian Society]], but later resigned.<ref>{{cite book |author=Ian Britain |title=Fabianism and culture: a study in British socialism and the arts c.1884–1918|url=https://archive.org/details/fabianismculture0000brit |url-access=registration |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1982 |isbn=0-521-23563-4 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/fabianismculture0000brit/page/7 7], 12 }}</ref> | |||

In the 1930s Gill became a supporter of [[social credit]]; later he moved towards a socialist position.<ref name="mc">{{cite book |author=Martin Ceadel |title=Pacifism in Britain, 1914–1945: The Defining of a Faith |location=Oxford |publisher=Clarendon Press |year=1980 |isbn=0-19-821882-6 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/pacifisminbritai0000cead/page/281 281, 289–91, 295, 321] |url=https://archive.org/details/pacifisminbritai0000cead/page/281 }}</ref> In 1934, Gill contributed art to an exhibition mounted by the left-wing [[Artists' International Association]], and defended the exhibition against accusations in ''[[The Catholic Herald]]'' that its art was "anti-Christian".<ref>{{cite book |author=Charles Harrison |title=English Art and Modernism 1900–1939 |location=London |publisher=Allen Lane |year=1981 |isbn=0-253-13722-5 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/englishartmodern0000harr/page/251 251–2] |url=https://archive.org/details/englishartmodern0000harr/page/251 }}</ref> | |||

Gill was adamantly opposed to [[fascism]], and was one of the few Catholics in Britain to openly support the [[Republican faction (Spanish Civil War)|Spanish Republicans]].<ref name="mc" /> Gill became a [[pacifist]] and helped set up the Catholic peace organisation Pax with [[E. I. Watkin]] and [[Donald Attwater]].<ref>{{cite book |author=Patrick G. Coy |title=A Revolution of the Heart: Essays on the Catholic Worker |location=Philadelphia |publisher=Temple University Press |year=1988 |isbn=0-87722-531-1 |page=[https://archive.org/details/revolutionofhear0000unse/page/76 76] |url=https://archive.org/details/revolutionofhear0000unse/page/76 }}</ref> Later Gill joined the [[Peace Pledge Union]] and supported the British branch of the [[Fellowship of Reconciliation]].<ref name="mc" /> | |||

==Personal life== | |||

In 1904, Gill married Ethel Hester Moore (1878–1961), with whom he had three daughters and an adopted son. In 1907, he moved with his family to "Sopers", a house in the village of [[Ditchling]] in Sussex, which would later become the centre of an artists' community inspired by Gill. Much of his work and memorabilia is held and on display at the [[Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft]]. | |||

[[File:Eric Gill - Eve (1929).jpg|thumb|upright|''Eve'', one of Gill's erotic wood engravings, 1929]] | |||

In 1913, Gill moved to Hopkin's Crank at Ditchling Common, two miles north of the village.<ref name="Font Designer – Eric Gill" >[http://www.linotype.com/391/ericgill.html ''Font Designer – Eric Gill ''] Retrieved 1 January 2009.</ref> The Common was an arts and crafts community focused around a chapel, with an emphasis on manual labour in opposition to modern commerce. He became a Roman Catholic in 1913 and worked primarily for Catholic clients. In 1921 he started a Catholic artists community called [[The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic]] and became a lay member of the [[Dominican Order]]. | |||

His personal diaries reveal that his religious beliefs did not limit his sexual activity, which included several extramarital affairs, incestuous sexual abuse of his two eldest teenage daughters, incestuous relationships with his sisters, and [[Zoophilia|sexual acts on his dog]].<ref name="fm">Fiona McCarthy, (17 October 2009). [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/oct/17/eric-gill-exhibition-fiona-maccarthy "Mad about sex."] ''[[The Guardian]]''. UK. Retrieved 17 October 2009.</ref><ref name=FMC2006>{{cite news |author=Fiona MacCarthy|url=http://arts.guardian.co.uk/features/story/0,,1826081,00.html |title=Written in stone |date=22 July 2006|accessdate=9 November 2017|work=The Guardian}}</ref><ref name=FRoher/> This aspect of Gill's life was little known beyond his family and friends until the publication of the 1989 biography by [[Fiona MacCarthy]]. An earlier biography by [[Robert Speaight]], published in 1966, mentioned none of it.<ref name=FMC2004>{{cite news |author=Fiona MacCarthy|url=https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/jul/24/art.biography |title=Baptism by fire |date=24 July 2004|accessdate=9 November 2017|work=The Guardian}}</ref> Gill's daughter Petra, who was alive at the time of the MacCarthy biography, denied the allegations but described her father as having "endless curiosity about sex" and that "we just took it for granted".<ref name="Nuttgens">{{cite web|author=Patrick Nuttgens|title=Petra Tegetmeier obituary|url=https://www.theguardian.com/news/1999/jan/06/guardianobituaries|date=6 January 1999|website=The Guardian|accessdate=19 February 2016}}</ref><ref name="The Darker Side of Ditchling">{{cite web|title=The Darker Side of Ditchling|date=9 January 1999|url=http://www.theargus.co.uk/news/5168823.DARKER_SIDE_OF_DITCHLING/|website=Brighton Argus|accessdate=19 February 2016}}</ref> Despite the acclaim the book received, and the widespread revulsion towards aspects of Gill's sexual life that followed publication, MacCarthy received some criticism for revealing Gill's incest in his daughter's lifetime.<ref name="Hoare">{{cite web|author=Lottie Hoare|date=9 January 1999|title=Petra Tegetmeier obituary|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/obituary-petra-tegetmeier-1045848.html|website=[[The Independent]]|accessdate=19 February 2016}}</ref><ref name="New York Times Harrison">{{cite web|author=Barbara Harrison|date=7 May 1989|title=A Lover's Quest for Art and God|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1989/05/07/books/perversity-raised-to-a-principle.html|website=The New York Times|accessdate=19 February 2016}}</ref> | |||

In 1924, Gill moved to the Monastery (built by Fr Ignatius) at [[Capel-y-ffin]] near [[Llanthony Abbey]] in Wales but soon tired of it, coming to feel that it had the wrong atmosphere and was too far from London, where most of his clients were. | |||

In 1928 he moved to Pigotts at [[Speen, Buckinghamshire|Speen]] near [[High Wycombe]] in Buckinghamshire<ref name="Font Designer – Eric Gill" /> where he lived for the rest of his life. | |||

Gill died of [[lung cancer]] in [[Harefield Hospital]] in [[Middlesex]] in 1940. He is buried in Speen churchyard. | |||

Gill's papers and library are archived at the [[William Andrews Clark Memorial Library]] at [[UCLA]] in California, designated by the Gill family as the repository for his manuscripts and correspondence.<ref name="WACML">{{cite web|title=Eric Gill Artwork Collection|url=http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c80g3jht/entire_text/|website=Online Archive of California|publisher=William Andrews Clark Memorial Library|accessdate=18 May 2016}}</ref> Some of the books in his collection have been digitised as part of the [[Internet Archive]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Gill, Eric, 1882–1940, former owner|url=https://archive.org/search.php?query=creator%3A%22Gill%2C+Eric%2C+1882-1940%2C+former+owner%22|website=Internet Archive|publisher=California Digital Library|accessdate=18 May 2016}}</ref> Additional archival and book collections related to Gill and his work reside at the [[University of Waterloo#Libraries and museums|University of Waterloo Library]]<ref name="WatSCA" /> and the University of Notre Dame's [[Hesburgh Library]].<ref name="NDSC">{{cite web|url=https://rarebooks.library.nd.edu/collections/fine_printing/gill.shtml|title=The Eric Gill Collection|website=University of Notre Dame Hesburgh Libraries|publisher=Rare Books & Special Collections|accessdate=18 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

==Contribution== | |||

As the revelations about Gill's private life reverberated, there was a reassessment of his personal and artistic achievement. As biographer Fiona MacCarthy sums up: | |||

{{quote |After the initial shock, [...] as Gill's history of adulteries, incest, and experimental connection with his dog became public knowledge in the late 1980s, the consequent reassessment of his life and art left his artistic reputation strengthened. Gill emerged as one of the twentieth century's strangest and most original controversialists, a sometimes infuriating, always arresting spokesman for man's continuing need of God in an increasingly materialistic civilization, and for intellectual vigour in an age of encroaching triviality.<ref name="maccarthy">{{cite encyclopedia |first=Fiona |last=MacCarthy |title=Gill, (Arthur) Eric Rowton (1882–1940) |encyclopedia=[[Oxford Dictionary of National Biography]] |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |year=2004 }}</ref>}} | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{Reflist}} | |||

== | ==Further reading== | ||

{{ | {{refbegin|40em}} | ||

*{{cite book|last=Attwater|first=Donald|title=A Cell of Good Living|place=London|publisher=G. Chapman|date=1969|isbn=0-225-48865-5}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Bringhurst|first=Robert|title=The Elements of Typographic Style|publisher=Hartley & Marks|date=1992|isbn=0-88179-033-8}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Collins|first=Judith|title=Eric Gill: The Sculpture|place=Woodstock, NY|publisher=Overlook Press|date=1998|isbn=0-87951-830-8}} | |||

*{{cite book|editor-last=Corey|editor-first=Steven|editor2-last=MacKenzie|editor2-first=Julia|title=Eric Gill: A Bibliography|publisher=St Paul's Bibliographies|date=1991|isbn=0-906795-53-2}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Dodd|first=Robin|title=From Gutenberg to OpenType|publisher=Hartley & Marks|date=2006|isbn=0-88179-210-1}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Fiedl|first=Frederich|first2=Nicholas|last2=Ott|first3=Bernard|last3=Stein|title=Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Through History|publisher=Black Dog & Leventhal|date=1998|isbn=1-57912-023-7|url=https://archive.org/details/typographyencycl00frie}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Fuller|first=Peter|title=Essay:Eric Gill,: a Man of Many Parts. Images of God, The Consolations of lost Illusions|publisher=Chatto & Windus|date=1985}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Gill|first=Cecil|first2=Beatrice|last2=Warde|first3=David|last3=Kindersley|title=The Life and Works of Eric Gill|series=Papers read at a Clark Library symposium, 22 April 1967|place=Los Angeles|publisher=William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California|date= 1968}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Gill|first=Evan|last2=Peace|first2=David (eds)|title=Eric Gill: The Inscriptions|publisher=Herbert Press|date=1994|isbn=1-871569-66-4}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Harling|first=Robert|title=The letter forms and type designs of Eric Gill|place=Westerham|publisher=Eva Svensson|date=1976|isbn=0-903696-04-5}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Holliday|first=Peter|title=Eric Gill in Ditchling|publisher=Oak Knoll Press|date=2002|isbn=1-58456-075-4}} | |||

*{{cite book|author=[[David Kindersley|Kindersley, David]]|title=Mr. Eric Gill: Further Thoughts by an Apprentice|publisher=Cardozo Kindersley Editions|orig-year=1967|date=1982|isbn=0-9501946-5-4}} | |||

*{{cite book|author=[[Fiona MacCarthy|MacCarthy, Fiona]]|title=Eric Gill|url=https://archive.org/details/ericgill0000macc|url-access=registration|publisher=Faber & Faber|date=1989|isbn=0-571-14302-4}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Macmillan|first=Neil|title=An A–Z of Type Designers|publisher=Yale University Press|date=2006|isbn=0-300-11151-7}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Miles|first=Jonathan|title=Eric Gill & David Jones at Capel-y-ffin|place=Bridgend, Mid Glamorgan|publisher=Seren Books|date=1992|isbn=1-85411-051-9}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Pincus|first=J.W|first2=W.|last2=Turner Berry|first3=A. F.|last3= Johnson|title=Encyclopædia of Type Faces|publisher=Cassell Paperback|place=London|date=2001|isbn=1-84188-139-2}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Skelton|first=Christopher (ed.)|title=Eric Gill – The Engravings|place=London|publisher=Herbert|date=1990|isbn=1-871569-15-X}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Speaight|first=Robert|title=Life of Eric Gill|url=https://archive.org/details/lifeofericgill0000spea|url-access=registration|place=London|publisher=Methuen & Co|date=1966|isbn= 0416286003}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Thorp|first=Joseph|title=Eric Gill|place=London|publisher=Jonathan Cape|date=1929|asin=B0008B8S9Q}} | |||

*{{cite book|last=Yorke|first=Malcolm|title=Eric Gill –Man of Flesh and Spirit|place=London|publisher=Constable|date=1981|isbn=0-09-463740-7|url=https://archive.org/details/ericgillmanoffle0000york}} | |||

{{refend}} | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

{{ | {{External links|date=July 2014}} | ||

*[http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person.php?LinkID=mp01776&role=art Portraits by Eric Gill] at the [[National Portrait Gallery (London)|National Portrait Gallery]]. | |||

*[http://www. | *[http://www.vads.ac.uk/results.php?cmd=advsearch&words=eric+gill&field=agent_name&oper=or&words2=&field2=all&mode=boolean&submit=search&CSC=1 Eric Gill] in the Crafts Study Centre. | ||

*[http://www. | *[http://www.vads.ac.uk/results.php?cmd=search&words=eric+gill+central+saint+martins+museum&mode=boolean Eric Gill] in the Central Saint Martins Museum and Study Collection. | ||

*[http:// | *[https://web.archive.org/web/20080509085558/http://www.sussex-southdowns-guide.com/Looking-for-Mr-Gill.html "Looking for Mr Gill"] BBC [[Storyville (television series)|Storyville]] Documentary on Eric Gill; filmed and directed by Luke Holland | ||

*[http:// | *[http://yourarchives.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php?title=Gill%2C_Eric_%281882-1940%29_Sculptor_and_Engraver Eric Gill] Article on The National Archives website which deals with many of Gill's works | ||

*[http://www. | *[http://www.ltmcollection.org/photos/index.html London Transport Museum Photographic Archive] | ||

*{{ | **{{ltmcollection|un/i0000dun.jpg|''North Wind'' at 55 Broadway}} | ||

| | **{{ltmcollection|ui/i0000dui.jpg|''East Wind'' at 55 Broadway}} | ||

| | **{{ltmcollection|uq/i0000duq.jpg|''South Wind'' at 55 Broadway}} | ||

| | *[http://www.mobileread.com/forums/showthread.php?t=206073 "An Essay on Typography"] PDF copy of the book by Eric Gill | ||

*[http://www.thingiverse.com/thing:528162/ 3D model of Gill's 1910-1 ''Ecstasy'' via photogrammetric survey] | |||

*[https://archive.org/details/twentyfivenudes00gill ''Twenty-five Nudes''], Gill, 1938 (collected drawings) | |||

*[https://archive.org/details/cu31924032565990 ''The Devil's Devices''], [[Hilary Douglas Clark Pepler|Douglas Pepler]], 1915 (woodcuts by Gill) | |||

*[https://archive.org/details/cu31924020596601 Manuscript & Inscription Letters], [[Edward Johnston]], 1909 (plates by Gill) | |||

*[http://www. | *[https://archive.org/details/troiluscriseyde00chau ''Troilus and Criseyde''], [[Geoffrey Chaucer]], translated by George Philip Knapp, 1932 (woodcuts by Gill) | ||

*[ | * {{FadedPage|id=Gill, Arthur Eric Rowton|name=Arthur Eric Rowton Gill (engraver)|author=yes}} | ||

{{Subject bar|commons=yes|commons-search=Category:Eric Gill|d=yes|q=yes|q-search=Eric Gill|d-search=Q551426}} | |||

{{Authority control}} | |||

{{ | |||

}} | |||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gill, Eric}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Gill, Eric}} | ||

[[Category:1882 births]] | [[index.php?title=Category:1882 births]] | ||

[[Category:1940 deaths]] | [[index.php?title=Category:1940 deaths]] | ||

[[Category: | [[index.php?title=Category:20th-century British printmakers]] | ||

[[Category:British sculptors]] | [[index.php?title=Category:20th-century British sculptors]] | ||

[[Category:British | [[index.php?title=Category:Academics of the Central School of Art and Design]] | ||

[[Category: | [[index.php?title=Category:Alumni of the Central School of Art and Design]] | ||

[[Category:Converts to Roman Catholicism]] | [[index.php?title=Category:Alumni of the Westminster School of Art]] | ||

[[Category:English Roman Catholics]] | [[index.php?title=Category:Arts and Crafts Movement]] | ||

[[Category: | [[index.php?title=Category:Associates of the Royal Academy]] | ||

[[Category: | [[index.php?title=Category:British architectural sculptors]] | ||

[[Category: | [[index.php?title=Category:British erotic artists]] | ||

[[Category: | [[index.php?title=Category:British letter cutters]] | ||

[[Category: | [[index.php?title=Category:British stamp designers]] | ||

[[Category: | [[index.php?title=Category:Burials in Berkshire]] | ||

[[index.php?title=Category:Child sexual abuse in England]] | |||

[[ | [[index.php?title=Category:Converts to Roman Catholicism]] | ||

[[ | [[index.php?title=Category:English anti-fascists]] | ||

[[ | [[index.php?title=Category:English graphic designers]] | ||

[[ | [[index.php?title=Category:English illustrators]] | ||

[[ | [[index.php?title=Category:English male sculptors]] | ||

[[ | [[index.php?title=Category:English pacifists]] | ||

[[index.php?title=Category:English Roman Catholics]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:English sculptors]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:English sex offenders]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:English socialists]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:English typographers]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:English wood engravers]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:Incest]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:Monumental masons]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:People from Brighton]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:People from Ditchling]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:South Downs artists]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:Stone carvers]] | |||

[[index.php?title=Category:Zoophilia]] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:40, 15 October 2024

Eric Gill | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait | |

| Born | Arthur Eric Rowton Gill 22 February 1882 Brighton, Sussex, England |

| Died | 17 November 1940 (aged 58) Middlesex, England |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Sculpture, typography |

| Movement | Arts and Crafts movement |

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill ARA (/ɡɪl/;[1] 22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, typeface designer, and printmaker, who was associated with the Arts and Crafts movement. His religious views and subject matter contrast with his sexual behaviour, including his erotic art, and (as mentioned in his own diaries) his extramarital affairs and sexual abuse of his daughters, sisters, and dog.

Gill was named Royal Designer for Industry, the highest British award for designers, by the Royal Society of Arts. He also became a founder-member of the newly established Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry.

Early life and studies

Gill was born in 1882 in Hamilton Road, Brighton, the second of the 13 children of (Cicely) Rose King (d. 1929), formerly a professional singer of light opera under the name Rose le Roi, and Rev. Arthur Tidman Gill, minister of the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion, who had recently left the Congregational church, after doctrinal disagreements. He was the elder brother of graphic artist MacDonald "Max" Gill (1884–1947).[2] In 1897 the family moved to Chichester.

Gill studied at Chichester Technical and Art School, and in 1900 moved to London to train as an architect with the practice of W. D. Caröe, specialists in ecclesiastical architecture.

Frustrated with his training, he took evening classes in stonemasonry at the Westminster Technical Institute and in calligraphy at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, where Edward Johnston, creator of the London Underground typeface, became a strong influence. In 1903 he gave up his architectural training to become a calligrapher, letter-cutter and monumental mason.[3][4][5]

Gill's first apprentice in 1906 was Joseph Cribb (1892–1967) a sculptor and letter carver, who came to Ditchling with Gill in 1907.[6] Hilary Stratton, was an apprentice sculptor between 1919 and 1921.[7]

Career

Sculpture

Working from Ditchling in Sussex, where he lived with his wife, in 1910 Gill began direct carving of stone figures. These included Madonna and Child (1910), which English painter and art critic Roger Fry described in 1911 as a depiction of "pathetic animalism", and Ecstasy (1911). Such semi-abstract sculptures showed Gill's appreciation of medieval ecclesiastical statuary, Egyptian, Greek and Indian sculpture, as well as the Post-Impressionism of Cézanne, van Gogh and Gauguin.[8]

His first public success was Mother and Child (1912). A self-described "disciple" of the Ceylonese philosopher and art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy, Gill was fascinated during this period by Indian temple sculpture.[9] Along with his friend and collaborator Jacob Epstein, Gill planned the construction in the Sussex countryside of a colossal, hand-carved monument in imitation of the large-scale Jain structures at Gwalior Fort in Madhya Pradesh, to which he had been introduced by William Rothenstein.[10]

In 1914, Gill produced sculptures for the stations of the cross in Westminster Cathedral.[11] In the same year, he met the typographer Stanley Morison. After the war, together with Hilary Pepler and Desmond Chute, Gill founded The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic at Ditchling. There his pupils included David Jones, who soon began a relationship with Gill's daughter, Petra.

Gill designed several war memorials after the First World War, including the Grade II* listed Trumpington War Memorial. Commissioned[when?] to produce a war memorial for the University of Leeds, Gill produced a frieze depicting Jesus driving the money-changers from the temple, showing contemporary Leeds merchants as the money-changers. Gill contended that the "money men" were a key cause of the war. This is at the Michael Sadler Building at the University.

In 1924, Gill moved to Capel-y-ffin in Powys, Wales, where he established a new workshop, to be followed by Jones and other disciples. In 1928, he set up a printing press and lettering workshop in Speen, Buckinghamshire. He took on a number of apprentices, including David Kindersley, who in turn became a successful sculptor and engraver, and his nephew, John Skelton, noted as an important letterer and sculptor. Other apprentices included Laurie Cribb, Donald Potter and Walter Ritchie.[12] Others in the household included Gill's two sons-in-law, Petra's husband Denis Tegetmeier and Joanna's husband Rene Hague.

In 1928–29, Gill carved three of eight relief sculptures on the theme of winds for Charles Holden's headquarters for the London Electric Railway (now Transport for London) at 55 Broadway, St James's. He carved a statue of the Virgin and Child for the west door of the chapel at Marlborough College.[13]

-

Nude woman naked reclining on a leopard skin, a graphite drawing by Gill (1928).

-

North Wind, 55 Broadway.

-

Ariel Between Wisdom and Gaiety, Broadcasting House, 1932.

-

Bas-relief in Lapworth parish church, 1928.

-

Relief representing Israelite culture, one of ten bas-reliefs by Gill in the inner courtyard at the Rockefeller Museum, Jerusalem, 1934.

In 1932, Gill produced a group of sculptures, Prospero and Ariel,[14] and others for the BBC's Broadcasting House in London. In 1934, Gill visited Jerusalem where he worked at the Palestine Archaeological Museum (now the Rockefeller Museum).[15] He carved a stone bas-relief of the meeting of Asia and Africa above the front entrance together with ten stone reliefs illustrating different cultures and a gargoyle fountain in the inner courtyard. He also carved stone signage throughout the museum in English, Hebrew and Arabic.

Gill was commissioned to produce a sequence of seven bas-relief panels for the façade of The People's Palace, now the Great Hall of Queen Mary University of London, which opened in 1936. In 1937, he designed the background of the first George VI definitive stamp series for the post office.[16][17] In 1938 Gill produced The Creation of Adam, three bas-reliefs in stone for the Palace of Nations, the League of Nations building in Geneva, Switzerland.[11] During this period he was made a Royal Designer for Industry, the highest British award for designers, by the Royal Society of Arts and became a founder-member of the Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry when it was established in 1938. In April 1937, Gill was elected an Associate member of the Royal Academy.[18]

Gill's only complete work of architecture was St Peter the Apostle Roman Catholic Church in Gorleston-on-Sea, built in 1938–39.

Midland Hotel, Morecambe

The Art Deco Midland Hotel was built in 1932–33 by the London Midland & Scottish Railway to the design of Oliver Hill and included works by Gill, Marion Dorn and Eric Ravilious.

For the project, Gill produced:

- two seahorses, modelled as Morecambe shrimps, for the outside entrance

- a round plaster relief on the ceiling of the circular staircase inside the hotel

- a decorative wall map of the north west of England

- a large stone relief of Odysseus being welcomed from the sea by Nausicaa.

Typefaces and inscriptions

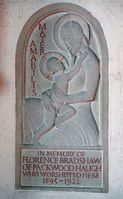

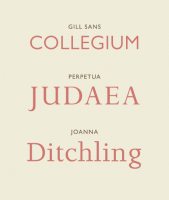

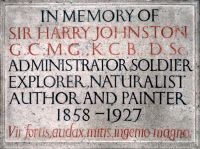

One of Gill's first independent lettering projects was creating an alphabet for W.H. Smith's sign painters. In 1925, he designed the Perpetua typeface, with the uppercase based upon monumental Roman inscriptions, for Morison, who was working for the Monotype Corporation. An in-situ example of Gill's design and personal cutting in the style of Perpetua can be found in the nave of the church in Poling, West Sussex, on a wall plaque commemorating the life of Sir Harry Johnston.

He designed the Gill Sans typeface in 1927–30, based on the sans-serif lettering originally designed for the London Underground. (Gill had collaborated with Edward Johnston in the early design of the Underground typeface, but dropped out of the project before it was completed.) In the period 1930–31, Gill designed the typeface Joanna which he used to hand-set his book, An Essay on Typography.

-

Specimens of typefaces by Eric Gill

-

Gill's type for the Golden Cockerel Press

-

Sir Harry Johnston memorial plaque

-

British Railways sign at Lowestoft railway station in Gill Sans

Gill carved these for a book, "Manuscript and Inscription Letters for Schools and Classes and for the Use of Craftsmen", compiled by his former teacher, Edward Johnston. He later gave them to the Victoria and Albert Museum so they could be used by students at the Royal College of Art.

Eric Gill's types include:

- Gill Sans, 1927–30; many variants followed

- Perpetua (design started c. 1925, first shown around 1929, commercial release 1932)

- Perpetua Greek (1929)[19]

- Golden Cockerel Press Type (for the Golden Cockerel Press; 1929)[20] Designed bolder than some of Gill's other typefaces to provide a complement to wood engravings.[21][22][23][24][25]

- Solus (1929)[26][20]

- Joanna (based on work by Granjon; 1930–31, not commercially available until 1958)

- Aries (1932)[20]

- Floriated Capitals (1932)[20]

- Bunyan (1934)

- Pilgrim (recut version of Bunyan; 1953)[20]

- Jubilee (also known as Cunard; 1934)[20]

These dates are somewhat debatable, since a lengthy period could pass between Gill creating a design and it being finalised by the Monotype drawing office team (who would work out many details such as spacing) and cut into metal.[27][28] In addition, some designs such as Joanna were released to fine printing use long before they became widely available from Monotype.

The family Gill Facia was created by Colin Banks as an emulation of Gill's stone carving designs, with separate styles for smaller and larger text.[29]

One of the most widely used British typefaces, Gill Sans, was used in the classic design system of Penguin Books and by the London and North Eastern Railway and later British Railways, with many additional styles created by Monotype both during and after Gill's lifetime.[27] In the 1990s, the BBC adopted Gill Sans for its wordmark and many of its on-screen television graphics.

Arabic

Gill was commissioned to develop a typeface with the number of allographs limited to what could be used on Monotype or Linotype machines. The typeface was loosely based on the Arabic Naskh style but was considered unacceptably far from the norms of Arabic script. It was rejected and never cut into type.[30][31][32]

Published works

Gill published numerous essays on the relationship between art and religion, and a number of erotic engravings.[33]

Some of Gill's published writings include:

- A Holy Tradition of Working: An Anthology of Writings[34]

- Clothes: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women[35]

- An Essay on Typography[36]

- Christianity and Art, 1927

- Art, 1934

- Work and Property, 1937[37]

- Work and Culture, 1938

- Twenty-five nudes, 1938[38]

- Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus[39]

- Notes on Postage Stamps[40]

- Christianity and the Machine Age, 1940.[41]

- On the Birmingham School of Art, 1940

Gill also provided woodcuts and illustrations for a range of other books.

Political views

As a young man, Gill was a member of the Fabian Society, but later resigned.[42]

In the 1930s Gill became a supporter of social credit; later he moved towards a socialist position.[43] In 1934, Gill contributed art to an exhibition mounted by the left-wing Artists' International Association, and defended the exhibition against accusations in The Catholic Herald that its art was "anti-Christian".[44]

Gill was adamantly opposed to fascism, and was one of the few Catholics in Britain to openly support the Spanish Republicans.[43] Gill became a pacifist and helped set up the Catholic peace organisation Pax with E. I. Watkin and Donald Attwater.[45] Later Gill joined the Peace Pledge Union and supported the British branch of the Fellowship of Reconciliation.[43]

Personal life

In 1904, Gill married Ethel Hester Moore (1878–1961), with whom he had three daughters and an adopted son. In 1907, he moved with his family to "Sopers", a house in the village of Ditchling in Sussex, which would later become the centre of an artists' community inspired by Gill. Much of his work and memorabilia is held and on display at the Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft.

In 1913, Gill moved to Hopkin's Crank at Ditchling Common, two miles north of the village.[4] The Common was an arts and crafts community focused around a chapel, with an emphasis on manual labour in opposition to modern commerce. He became a Roman Catholic in 1913 and worked primarily for Catholic clients. In 1921 he started a Catholic artists community called The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic and became a lay member of the Dominican Order.

His personal diaries reveal that his religious beliefs did not limit his sexual activity, which included several extramarital affairs, incestuous sexual abuse of his two eldest teenage daughters, incestuous relationships with his sisters, and sexual acts on his dog.[46][47][11] This aspect of Gill's life was little known beyond his family and friends until the publication of the 1989 biography by Fiona MacCarthy. An earlier biography by Robert Speaight, published in 1966, mentioned none of it.[48] Gill's daughter Petra, who was alive at the time of the MacCarthy biography, denied the allegations but described her father as having "endless curiosity about sex" and that "we just took it for granted".[49][50] Despite the acclaim the book received, and the widespread revulsion towards aspects of Gill's sexual life that followed publication, MacCarthy received some criticism for revealing Gill's incest in his daughter's lifetime.[51][52]

In 1924, Gill moved to the Monastery (built by Fr Ignatius) at Capel-y-ffin near Llanthony Abbey in Wales but soon tired of it, coming to feel that it had the wrong atmosphere and was too far from London, where most of his clients were.

In 1928 he moved to Pigotts at Speen near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire[4] where he lived for the rest of his life.

Gill died of lung cancer in Harefield Hospital in Middlesex in 1940. He is buried in Speen churchyard.

Gill's papers and library are archived at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library at UCLA in California, designated by the Gill family as the repository for his manuscripts and correspondence.[5] Some of the books in his collection have been digitised as part of the Internet Archive.[53] Additional archival and book collections related to Gill and his work reside at the University of Waterloo Library[3] and the University of Notre Dame's Hesburgh Library.[54]

Contribution

As the revelations about Gill's private life reverberated, there was a reassessment of his personal and artistic achievement. As biographer Fiona MacCarthy sums up:

After the initial shock, [...] as Gill's history of adulteries, incest, and experimental connection with his dog became public knowledge in the late 1980s, the consequent reassessment of his life and art left his artistic reputation strengthened. Gill emerged as one of the twentieth century's strangest and most original controversialists, a sometimes infuriating, always arresting spokesman for man's continuing need of God in an increasingly materialistic civilization, and for intellectual vigour in an age of encroaching triviality.[55]

References

- ↑ Olausson, Lena; Sangster, Catherine (2006). Oxford BBC Guide to Pronunciation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-19-280710-6.

- ↑ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (23 September 2004), "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography", The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, pp. ref:odnb/33403, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33403, retrieved 12 December 2019

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Eric Gill archival and book collection". University of Waterloo Library. Special Collections & Archives. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Font Designer – Eric Gill Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Eric Gill Artwork Collection". Online Archive of California. William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Historic England. "Ditchling War Memorial (1438295)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ↑ Sussex Life article by Vida Herbison, Sussex sculptor and stonemason, undated article c 1975

- ↑ "Eric Gill – Tate". Tate. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ Video of a Lecture at London University detailing Gill's interest in Indian Sculpture, London University School of Advanced Study, March 2012.

- ↑ Rupert Richard Arrowsmith (2010). Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African, and Pacific Art and the London Avant-Garde. Oxford University Press. pp. 74–103. ISBN 978-0-19-959369-9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Finlo Roher (5 September 2007). "Can the art of a paedophile be celebrated ?". BBC News. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ↑ C.f. Donald Potter, My Time with Eric Gill: A Memoir, Gamecock Press, 1980, ISBN 0-9506205-1-3.

- ↑ "Art & Architecture". marlboroughcollege.org. 20 July 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ Illustration.

- ↑ "Eric Gill, 1882–1940". East Meets West: The Story of the Rockefeller Museum. Israel Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ Peter Worsfold, Great Britain King George VI Low Value Definitive Stamps, The Great Britain Philatelic Society, 2001, ISBN 0-907630-17-0. The effigy of George VI was drawn by Edmund Dulac, who had a debate with Gill in newspapers about stamp designing after the Edward VIII postage stamps late-1936, quoted in Colin White, Edmund Dulac, Studio Vista, 1977, p. 172.

- ↑ "Eric Gill Postage Stamps by Type Designer". The Offices of Kat Ran Press. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ "Royal Academy of Arts collections, Eric Gill, A.R.A". Royal Academy of Arts. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ Robert Harling (1978). The Letter Forms and Type Designs of Eric Gill. Boston, MA: Eva Svensson and David R. Godine. ISBN 0-87923-200-5.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 "Eric Gill (1882-1940), Fonts designed by Eric Gill". Identifont. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ↑ Mosley, James. "Eric Gill and the Cockerel Press". Upper & Lower Case. International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Brignall, Colin. "The Digital Development of ITC Golden Cockerel". International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Carter, Sebastian. "The Golden Cockerel Press, Private Presses and Private Types". International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Dreyfus, John. "Robert Gibbings and the quest for types suitable for illustrated books". International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Yoseloff, Thomas. "A Publisher's Story". International Typeface Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Bates, Keith. "The Non Solus Story". K-Type. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Rhatigan, Dan. "Gill Sans after Gill" (PDF). Monotype. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ↑ Rhatigan, Dan. "Time and Times again". Monotype. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ↑ Banks, Colin. "Gill Facia MT". Fontshop. Monotype. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ Blair, S.S. Islamic Calligraphy. p. 606, Fig. 13.7.

- ↑ Graalfs, Gregory (1998). "Gill Sands". Print.

- ↑ "Eric Gill" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 41 (3). 1958. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ Christopher Skelton (ed.), Eric Gill, The Engravings, Herbert Press, 1990, ISBN 1-871569-15-X.

- ↑ Gill, Eric. (1983). A Holy Tradition of Working: An Anthology of Writings Golgonooza Press. ISBN 0-903880-30-X.

- ↑ Cape, Jonathan. (1931). Jonathan Cape. Gill contributed: Clothes: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women

- ↑ Gill, Eric. (1931). An Essay on Typography ISBN 0-87923-762-7, ISBN 0-87923-950-6 (reprints).

- ↑ Gill, Eric. (1937). Trousers & The Most Precious Ornament. London: Faber and Faber. oclc 5034115

- ↑ Gill, Eric (1951). "Twenty-Five Nudes". J M Dent & Sons. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ↑ Jonathan Cape, 1940 (published posthumously) Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus. ISBN 1-870495-13-6

- ↑ Gill, Eric. (2011). Notes on Postage Stamps Kat Ran Press, 2011. ISBN 0-9794342-1-1.

- ↑ In the series Christian Newsletter Books, The Sheldon Press.

- ↑ Ian Britain (1982). Fabianism and culture: a study in British socialism and the arts c.1884–1918. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7, 12. ISBN 0-521-23563-4.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Martin Ceadel (1980). Pacifism in Britain, 1914–1945: The Defining of a Faith. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 281, 289–91, 295, 321. ISBN 0-19-821882-6.

- ↑ Charles Harrison (1981). English Art and Modernism 1900–1939. London: Allen Lane. pp. 251–2. ISBN 0-253-13722-5.

- ↑ Patrick G. Coy (1988). A Revolution of the Heart: Essays on the Catholic Worker. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-87722-531-1.

- ↑ Fiona McCarthy, (17 October 2009). "Mad about sex." The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ↑ Fiona MacCarthy (22 July 2006). "Written in stone". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ Fiona MacCarthy (24 July 2004). "Baptism by fire". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ↑ Patrick Nuttgens (6 January 1999). "Petra Tegetmeier obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ "The Darker Side of Ditchling". Brighton Argus. 9 January 1999. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ Lottie Hoare (9 January 1999). "Petra Tegetmeier obituary". The Independent. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ Barbara Harrison (7 May 1989). "A Lover's Quest for Art and God". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ "Gill, Eric, 1882–1940, former owner". Internet Archive. California Digital Library. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Eric Gill Collection". University of Notre Dame Hesburgh Libraries. Rare Books & Special Collections. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ MacCarthy, Fiona (2004). "Gill, (Arthur) Eric Rowton (1882–1940)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Attwater, Donald (1969). A Cell of Good Living. London: G. Chapman. ISBN 0-225-48865-5.

- Bringhurst, Robert (1992). The Elements of Typographic Style. Hartley & Marks. ISBN 0-88179-033-8.

- Collins, Judith (1998). Eric Gill: The Sculpture. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-830-8.

- Corey, Steven; MacKenzie, Julia, eds. (1991). Eric Gill: A Bibliography. St Paul's Bibliographies. ISBN 0-906795-53-2.

- Dodd, Robin (2006). From Gutenberg to OpenType. Hartley & Marks. ISBN 0-88179-210-1.

- Fiedl, Frederich; Ott, Nicholas; Stein, Bernard (1998). Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Through History. Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 1-57912-023-7.

- Fuller, Peter (1985). Essay:Eric Gill,: a Man of Many Parts. Images of God, The Consolations of lost Illusions. Chatto & Windus.

- Gill, Cecil; Warde, Beatrice; Kindersley, David (1968). The Life and Works of Eric Gill. Papers read at a Clark Library symposium, 22 April 1967. Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California.

- Gill, Evan; Peace, David (eds) (1994). Eric Gill: The Inscriptions. Herbert Press. ISBN 1-871569-66-4.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Harling, Robert (1976). The letter forms and type designs of Eric Gill. Westerham: Eva Svensson. ISBN 0-903696-04-5.

- Holliday, Peter (2002). Eric Gill in Ditchling. Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 1-58456-075-4.

- Kindersley, David (1982) [1967]. Mr. Eric Gill: Further Thoughts by an Apprentice. Cardozo Kindersley Editions. ISBN 0-9501946-5-4.

- MacCarthy, Fiona (1989). Eric Gill. Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-14302-4.

- Macmillan, Neil (2006). An A–Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11151-7.

- Miles, Jonathan (1992). Eric Gill & David Jones at Capel-y-ffin. Bridgend, Mid Glamorgan: Seren Books. ISBN 1-85411-051-9.

- Pincus, J.W; Turner Berry, W.; Johnson, A. F. (2001). Encyclopædia of Type Faces. London: Cassell Paperback. ISBN 1-84188-139-2.

- Skelton, Christopher (ed.) (1990). Eric Gill – The Engravings. London: Herbert. ISBN 1-871569-15-X.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Speaight, Robert (1966). Life of Eric Gill. London: Methuen & Co. ISBN 0416286003.

- Thorp, Joseph (1929). Eric Gill. London: Jonathan Cape. ASIN B0008B8S9Q.

- Yorke, Malcolm (1981). Eric Gill –Man of Flesh and Spirit. London: Constable. ISBN 0-09-463740-7.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (July 2014) |

- Portraits by Eric Gill at the National Portrait Gallery.

- Eric Gill in the Crafts Study Centre.

- Eric Gill in the Central Saint Martins Museum and Study Collection.

- "Looking for Mr Gill" BBC Storyville Documentary on Eric Gill; filmed and directed by Luke Holland

- Eric Gill Article on The National Archives website which deals with many of Gill's works

- London Transport Museum Photographic Archive

- "An Essay on Typography" PDF copy of the book by Eric Gill

- 3D model of Gill's 1910-1 Ecstasy via photogrammetric survey

- Twenty-five Nudes, Gill, 1938 (collected drawings)

- The Devil's Devices, Douglas Pepler, 1915 (woodcuts by Gill)

- Manuscript & Inscription Letters, Edward Johnston, 1909 (plates by Gill)

- Troilus and Criseyde, Geoffrey Chaucer, translated by George Philip Knapp, 1932 (woodcuts by Gill)

- Works by Arthur Eric Rowton Gill (engraver) at Faded Page (Canada)

Script error: No such module "subject bar".

index.php?title=Category:1882 births

index.php?title=Category:1940 deaths

index.php?title=Category:20th-century British printmakers

index.php?title=Category:20th-century British sculptors

index.php?title=Category:Academics of the Central School of Art and Design

index.php?title=Category:Alumni of the Central School of Art and Design

index.php?title=Category:Alumni of the Westminster School of Art

index.php?title=Category:Arts and Crafts Movement

index.php?title=Category:Associates of the Royal Academy

index.php?title=Category:British architectural sculptors

index.php?title=Category:British erotic artists

index.php?title=Category:British letter cutters

index.php?title=Category:British stamp designers

index.php?title=Category:Burials in Berkshire

index.php?title=Category:Child sexual abuse in England

index.php?title=Category:Converts to Roman Catholicism

index.php?title=Category:English anti-fascists

index.php?title=Category:English graphic designers

index.php?title=Category:English illustrators

index.php?title=Category:English male sculptors

index.php?title=Category:English pacifists

index.php?title=Category:English Roman Catholics

index.php?title=Category:English sculptors

index.php?title=Category:English sex offenders

index.php?title=Category:English socialists

index.php?title=Category:English typographers

index.php?title=Category:English wood engravers

index.php?title=Category:Incest

index.php?title=Category:Monumental masons

index.php?title=Category:People from Brighton

index.php?title=Category:People from Ditchling

index.php?title=Category:South Downs artists

index.php?title=Category:Stone carvers

index.php?title=Category:Zoophilia

- Pages with broken file links

- CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Candidates for deletion

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Use British English from August 2014

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Use dmy dates from July 2020

- Articles without Wikidata item

- Articles with hCards

- All articles with vague or ambiguous time

- Vague or ambiguous time from July 2015

- CS1 errors: generic name

- Wikipedia external links cleanup from July 2014

- Wikipedia spam cleanup from July 2014

- Articles with Project Gutenberg links

- AC with 0 elements

- Pages with red-linked authority control categories