History of zoophilia: Difference between revisions

History of zoophilia>WikiCleanerBot m v2.05b - Bot T20 CW#61 - Fix errors for CW project (Reference before punctuation) |

m 1 revision imported |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 20:43, 28 November 2023

The history of zoophilia and bestiality begins in the prehistoric era, where depictions of humans and non-human animals in a sexual context appear infrequently in European rock art.[1] Bestiality remained a theme in mythology and folklore through the classical period and into the Middle Ages (e.g. the Greek myth of Leda and the Swan)[2] and several ancient authors purported to document it as a regular, accepted practice—albeit usually in "other" cultures.

Explicit legal prohibition of human sexual contact with other animals is a legacy of the Abrahamic religions:[2] the Hebrew Bible imposes the death penalty on both the person and animal involved in an act of bestiality.[3] There are several examples known from medieval Europe of people and animals executed for committing bestiality. With the Age of Enlightenment, bestiality was subsumed with other sexual "crimes against nature" into civil sodomy laws, usually remaining a capital crime.

Bestiality remains illegal in most countries. Arguments used to justify this include: it is against religion, it is a "crime against nature," and that non-human animals cannot give consent and that sex with animals is inherently abusive.[4] In common with many paraphilias, the internet has provided a connective platform for the zoophile community, which has lobbied for the recognition of zoophilia (or zoosexuality as an alternative sexuality), and advocated for the legalisation of bestiality.[5]

Prehistory

Depictions of human sexual activity with animals appear infrequently in prehistoric art. Possibly the oldest depiction, and the only known example from the Palaeolithic (prior to the domestication of animals), is found in the Vale do Côa in Portugal. It shows a man with an exaggerated, erect penis juxtaposed with a goat. However, there is some doubt that the two figures are contemporary; while the goat is depicted in characteristic palaeolithic style, the scene may have been altered in a later period with the insertion of the human figure.[6]

From the Neolithic onwards, images of zoophilia are slightly more common. Examples are found at Coren del Valento, a cave in Val Camonica, Italy, containing rock art dating from 10,000 BCE to as late as the Middle Ages, one depicting a man penetrating a horse,[7] and Sagaholm, a Bronze Age cairn in Sweden where several petroglyphs have been found with similar scenes.[8]

Classical antiquity

Several Greek myths include the God Zeus seducing or abducting favoured mortals while in the form of an animal: Europa and the bull, Ganymede and the eagle, and Leda and the Swan.[2] Only the latter legend includes actual copulation between Leda and Zeus in his animal form, but depictions of this act, fairly uncommon in antiquity, became a popular motif in classicising Renaissance art, contributing to a lasting prominence in Western culture.[9]

Various classical writers recorded that bestiality was common in other cultures. Herodotus was followed by Pindar, Strabo and Plutarch[citation needed] in alleging that Egyptian women engaged in sexual relations with goats for religious and magical purposes – the animal aspects of Egyptian deities being particularly alien to the Greco-Roman world.[10][11] Conversely, Plutarch and Virgil make similar accusations of the Greeks.

Despite their place in mythology and literature, actual acts of bestiality were probably as uncommon in antiquity as they are today.[2] Roman civil law, however, made no mention of it.[12] The explicit prohibition of and strict penalties for zoophilia universal in later European legal systems were derived from Jewish and Christian tradition.[2] The Hebrew Bible imposes the death penalty on both the human and animal parties involved in an act of bestiality: "if a man has sexual relations with an animal, he shall be put to death; and you shall kill the animal."[3] The Synod of Ancyra in 313–316 discussed the position of the church with regard to bestiality at length and two of the resulting twenty-five canons addressed it: the sixteenth canon described the penance and level of restrictions to be applied to various age groups for committing bestiality; the seventeenth canon prohibited all lepers from praying inside church if they had committed bestiality while they suffered from leprosy.[13]

Hittite law mandated the death penalty for intercourse with animals, excluding horses and mules (violators were instead barred from the priesthood and from approaching the king).[14]

Europe: Middle Ages

In the Church-oriented culture of the Middle Ages, zoosexual activity was met with execution, typically burning, and death to the animals involved either the same way or by hanging.[citation needed] Sects deemed heretical by the Church such as the Hussites were accused of bestiality.[15] Masters comments that:

- "Theologians, bowing to Biblical prohibitions and basing their judgements on the conception of man as a spiritual being and of the animal as a merely carnal one, have regarded the same phenomenon as both a violation of Biblical edicts and a degradation of man, with the result that the act of bestiality has been castigated and anathematized [...]"[citation needed]

In 1468, Jean Beisse, accused of bestiality with a cow on one occasion and a goat on another, was first hanged, then burned. The animals involved were also burned. In 1539, Guillaume Garnier, charged with intercourse with a female dog (described as "sodomy"), was ordered strangled after he confessed under torture. The dog was burned, along with the trial records which were "too horrible and potentially dangerous to be permitted to exist" (Masters). Other accusations of bestiality in the period include the trials of Thomas Weir[16][17][18] and John Atherton.[19][20][21] In 1601, Claudine de Culam, a young girl of sixteen, was convicted of copulating with a dog. Both the girl and the dog were first hanged, and finally burned. In 1735, François Borniche was charged with sexual intercourse with animals. It was greatly feared that "his infamous debauches may corrupt the young men." He was imprisoned, and there is no record of his release.[citation needed] Historians claim there were more than a thousand executions recorded for bestiality in Sweden throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.[22][23]

On the other hand, other accounts are more possibly fictitious, such as Pietro Damiani's, who in his "De bono religiosi status et variorum animatium tropologia" (11th century) tells of a Count Gulielmus whose pet ape became his wife's lover. One day the ape became "mad with jealousy" on seeing the count lying with his wife that it fatally attacked him. Damiani claims he was told about this incident by Pope Alexander II and shown an offspring claimed to be that of the ape and woman. (Illustrated Book of Sexual Records)[citation needed]

Clergyman and chronicler Gerald of Wales claimed to have witnessed a man having intercourse with a horse as part of a pagan ritual in Ireland.[24][25]

Although thousands of female witches were accused of having sex with animals, usually said to be the Devil in animal form or their familiars, court records available in Europe and the United States, dating back to the 14th century and continuing into the 20th century, nearly always show males, rather than females, as the human parties in court cases. (Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality, Humboldt University)[citation needed]

French Revolution and legal reform

From at least the 13th century and until the French Revolution, French criminal law had theoretically punished bestiality with death (burning at the stake), although in practice law courts only occasionally meted out that penalty. When the revolutionary politicians of the National Constituent Assembly set out to remake French government and society, their reforms included new criminal laws liberalizing sexual activities, inspired by ideas of the 18th-century Enlightenment. In 1791, Louis-Michel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau presented a newly drafted penal code to the National Constituent Assembly. He explained that it outlawed only "true crimes" and not "phoney offenses, created by superstition, feudalism, the tax system, and [royal] despotism." Zoophilia was not mentioned in the new Penal Code (promulgated September 26-October 6, 1791) and thus decriminalized it.[26][27]

19th-Century

In 1835, the Russian Empire criminalized skotolozhstvo (bestiality) in the country. In 1845, the Russian Empire merged both muzhelozhstvo (sodomy) and skotolozhstvo statues together into a single statue prohibiting protivoestestvennye poroki (vices contrary to nature).[28] On August 20, 1848, Norway adopted new penal codes which replaced a 1687 law that implemented the capital punishment by burning for "intercourse which is against nature" (bestiality) and reduced the punishment for engaging in bestiality from capital punishment to a sentence of hard labor of the fifth degree.[29]

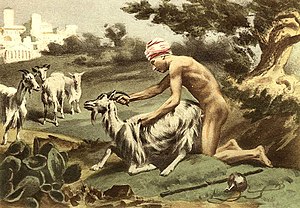

In 1855, the German physician Wilhelm Gollmann claimed that sodomy was initially committed by shepherds. He adds that shepherds were drawn to this method of pleasure for the "want of more natural opportunities." Gollmann then prejudicially attacks Sicilians, whom he claims commit zoophilia against goats. According to Blumenbach, the females of Guinea commit indecent acts against monkeys. Gollmann finalizes his dubious claims with his assertion that Iranians commit acts against donkeys as a cure for coxalgia.[30]

In 1852, the Austrian Empire enacted § 130 which criminalized bestiality with a maximum of five years in prison. About fifty people were convicted annually due to the law.[31] In 1861, the Offences against the Person Act 1861 lowered the criminal penalty of buggery in the United Kingdom from the death penalty to life in prison.[27] On February 10, 1866, Denmark (including Greenland and Faroes) adopted new penal codes which replaced a 1683 law that implemented the death penalty at the stake by means of royal pardon for "intercourse against nature" (bestiality) and reduced the punishment for engaging in bestiality from capital punishment to a sentence of hard labor ranging from about eight months to six years, which was further reduced with about one third if the penalty was served in solitude.[29] On June 25, 1869, Iceland adopted a new penal code that replaced a 13th-century law mandating death by burning for "intercourse which is against nature" (bestiality) to a punishment of work in a house of correction.[29]

On May 15, 1871, the German Empire enacted Paragraph 175 into the “Reichs-Criminal Code” (RStGB) which outlawed zoophilia and punished it by imprisonment.[31][32] In 1878, the penal code of the Kingdom of Hungary criminalized bestiality with a maximum of one year in prison.[27] Sweden, in 1864, and Grand Duchy of Finland, on December 19, 1889, adopted new penal codes replacing and a 1734 penal code, which applied to both countries and criminalized bestiality with being burnt at the stake. The 1864 Swedish law punished "fornication with animals" (bestiality) with two years hard labor, while the 1889 Finished law punished bestiality with imprisonment for two years.[29]

20th-Century

On June 28, 1935, Nazi Germany enacted legislation that created a separate category in Paragraph 175 for "fornication with animals" and penalized with up to five years in prison.[31]

During the 20th century, zoophilia was legalized in the Russian Empire in 1903,[28] in Denmark (including Greenland and Faroes) on January 1, 1933,[29][33] in Iceland on August 12, 1940,[29] in Sweden in 1944,[34] in Hungarian People's Republic in 1961, in West Germany in 1969,[31] in Austria in 1971,[31] in Finland on January 15, 1971,[29][35] and Norway on April 21, 1972.[29]

21st-Century

In 2003, the Sexual Offences Act 2003 lowered the criminal penalty of bestiality in the United Kingdom from life in prison to two years in prison.[36]

In 2006, Denmark's Council for Animal Ethics said there was no need to ban bestiality unless it took place in pornographic films or sex shows. Only one of the 10 members of the council, set up by the Danish Justice Ministry to establish and uphold animal ethics, wanted bestiality expressly prohibited. The other members said current laws provided enough animal protection.[37] Denmark outlawed bestiality in 2015 after all parties except the Liberal Alliance voted in support of a ban, leaving Hungary, Finland and Romania as the only European Union countries without bans on bestiality.[38]

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (November 2023) |

During the 21st century, bestiality was re-criminalized in the following countries or territories: Iowa (illegal since 2001),[39] Maine (illegal since 2001),[40] Oregon (illegal since 2001),[41] Illinois (illegal since January 1, 2003),[42][43] Maryland (illegal since October 1, 2002),[44][45] South Dakota (illegal since July 1, 2003),[46][47][48] France (illegal since March 10, 2004),[49] Washington (illegal since June 7, 2006),[50][51] Arizona (illegal since September 21, 2006),[52][53][54] Belgium (illegal since May 11, 2007),[55][56][57] Colorado (illegal since July 1, 2007),[58][59][60] Indiana (illegal since July 1, 2007),[61][62] Tennessee (illegal since July 1, 2007),[63][64] Netherlands (illegal since 2010),[65] Norway (illegal since January 1, 2010),[66] Alaska (illegal since September 13, 2010),[67][68] Australian Capital Territory (illegal since 2011),[69] Florida (illegal since October 1, 2011),[70][71][72] Germany (illegal since 2013),[73] Sweden (illegal since January 1, 2014),[74] Denmark (illegal since April 2015),[38] and New Mexico (since June 2023).[75]

See also

References

- ↑ Bahn, Paul G. (1998). The Cambridge illustrated history of prehistoric art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-521-45473-5. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cornog, M.; Perper, T. (1994). "Bestiality". In Haeberle, E. J.; Bullough, B. L.; Bullough; et al. (eds.). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. New York & London: Garland. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Leviticus 20:15

- ↑ Regan, Tom. Animal Rights, Human Wrongs. Rowman & Littlefield, 2003, pp. 63-4, 89.

- ↑ Francis, Thomas (20 August 2009). "Those Who Practice Bestiality Say They're Part of the Next Sexual Rights Movement". Broward Palm Beach New Times. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Angulo Cuesta, J.; García Diez, M. (2006). "Diversity and meaning of Palaeolithic phallic male representations in Western Europe". Actas Urol Esp. 30 (3): 254–267. Archived from the original on 2012-07-26.

- ↑ Anati, E. (2008). "The Way of Life Recorded in the Rock Art of Valcamonica" (PDF). Adoranten (2008). Scandinavian Society for Prehistoric Art. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-19.

- ↑ "Sagaholm". On the rocks. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Bull, M. (2005). The Mirror of the Gods, How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan Gods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-521923-6.

- ↑ Ray, J. D. (2002). "Animal Cults". In Redford, D. B. (ed.). The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-19-515401-6.

- ↑ Leavitt, J. (1992). "The Cults of Isis among the Greeks and in the Roman Empire". In Bonnefoy, Y. (ed.). Greek and Egyptian Mythologies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-226-06454-3.

- ↑ Norton, R. "Of Sodomy and Bestiality". Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "THE COUNCIL OF ANCYRA, HISTORICAL NOTE & CANONS". Archived from the original on 13 February 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ The Code of the Nesilim, c. 1650-1500 BCE Retrieved 24 July 2013

- ↑ Out Of Print; Marmor, J. (1980). Homosexual Behavior. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03045-3. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- ↑ Raffe, Alasdair (2012). The Culture of Controversy: Religious Arguments in Scotland, 1660-1714. ISBN 9781843837299.

- ↑ Henderson, Lizanne (8 April 2016). Witchcraft and Folk Belief in the Age of Enlightenment: Scotland, 1670-1740. ISBN 9781137313249.

- ↑ Quilligan, Maureen (7 June 2011). Incest and Agency in Elizabeth's England. ISBN 978-0812203301.

- ↑ Marmion, Anthony (June 2013). The Ancient and Modern History of the Maritime Ports of Ireland. ISBN 9783954273522.

- ↑ Wirrig, Adam L. (4 April 2022). Trial of Translation: An Examination of 1 Corinthians 6:9 in the Vernacular Bibles of the Early Modern Period. ISBN 9781725277557.

- ↑ Gibson, William; Begiato, Joanne (28 February 2017). Sex and the Church in the Long Eighteenth Century: Religion, Enlightenment and the Sexual Revolution. ISBN 9781786731579.

- ↑ Österberg, E. (2010). Friendship and Love, Ethics and Politics: Studies in Mediaeval and Early Modern History. The Natalie Zemon Davis Annual Lectures Series. Central European University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-615-5211-79-9. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ↑ Krogh, T. (2011). A Lutheran Plague: Murdering to Die in the Eighteenth Century. Studies in Central European Histories. Brill. p. 59. ISBN 978-90-04-22137-6. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

- ↑ Last Night's Television: Always let a sleeping pagan lie

- ↑ Banks-Smith, Nancy (July 20, 2004). "Please, please tell me now". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ↑ Napoleonic Code Archived 2014-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Bestiality and Zoophilia: Sexual Relations with Animals

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 The Keys to Happiness: Sex and the Search for Modernity in Fin-de-siècle Russia

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 Rydström, Jens (May 31, 2007). Criminally Queer: Homosexuality and Criminal Law in Scandinavia 1842-1999. ISBN 9789052602455. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ↑ Gollmann, Wilhelm (1854). Homeopathic Guide to all Diseases Urinary and Sexual Organ. Charles Julius Hempel. Rademacher & Sheek.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Sexuality with Animals (Zoophilia) – an Unrecognized Problem in Animal Welfare Legislation Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Chicago Whispers: A History of LGBT Chicago before Stonewall

- ↑ Animal Slaughter is Illegal in Denmark but Animal Prostitution Is Not

- ↑ Sweden Considering Ban On Beastiality

- ↑ Kilpinen, Pekka (2001). "Järjettömäin luondocappalden canssa". University of Helsinki (in suomi). Archived from the original on 20 March 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ Intercourse with an animal

- ↑ Animal sex proposal spurs call for referendum

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Denmark passes law to ban bestiality". BBC Newsbeat. 22 April 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ↑ 717C.1. Bestiality

- ↑ Maine

- ↑ 167.333. Sexual assault of animal

- ↑ Erickson, Kurt (July 27, 2002). "Ryan signs anti-bestiality legislation - The Pantagraph Bloomington". HighBeam Research. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ↑ 5/12-35. Sexual conduct or sexual contact with an animal

- ↑ § 3-322. Unnatural or perverted sexual practice

- ↑ 2002 Regular Session HOUSE BILL 11

- ↑ § 22-22-42. Bestiality--Acts constituting--Commission a felony

- ↑ "House Bill 1061". Archived from the original on 2016-04-17. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ Effective Dates for Legislation Archived 2015-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ [French Penal Code - Chapter one: Serious abuse or acts of cruelty animals. - Article 521-1]

- ↑ SB 6417 - 2005-06

- ↑ 16.52.205. Animal cruelty in the first degree

- ↑ SB1160 community facilities districts; financing (NOW: animal welfare; rescue; bestiality)

- ↑ "General Effective Dates". Archived from the original on 2010-05-14. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ § 13-1411. Bestiality; classification; definition

- ↑ La zoophilie interdite

- ↑ Violent and extreme pornography Archived 2013-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Lois, Decrets, Ordonnances Et Reglements / Wetten, Decreten, Ordonnanties En Verordeningen". Moniteur Belge / Belgisch Staatsblad: 38259–38260. 13 July 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2014. (in French and Dutch)

- ↑ Summarized History for Bill Number HB07-1235

- ↑ "H.B. 07-1235 Cruelty to animals - impounded and forfeited animals - euthanasia - dangerous dogs - property damage - sexual act with animal - injured animals - euthanasia - domestic violence - violation of court order protecting animals - aggravated animal cruelty offenders - genetic testing". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

- ↑ § 18-9-202. Cruelty to animals--aggravated cruelty to animals--cruelty to a service animal--restitution

- ↑ 35-46-3-14 Bestiality

- ↑ Action List: House Bill 1387

- ↑ *SB 0487 by *Finney R. ( HB 0953 by *Maggart)

- ↑ 39-14-214. Criminal offenses against animals.

- ↑ "wetten.nl - Wet- en regelgeving - Wetboek van Strafrecht - BWBR0001854" (in Nederlands). Wetten.overheid.nl. 2012-12-24. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ↑ "New Animal Welfare Act". regjeringen.no. 15 May 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ Sec. 11.61.140 Cruelty to animals.

- ↑ "Alaska State Legislature".

- ↑ "Crimes Legislation Amendment Bill 2010" (PDF). Australian Capital Territory Legislation Register. 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ↑ SB 344 - Animal Cruelty

- ↑ CS/HB 125 - Animal Cruelty

- ↑ 828.126 Sexual activities involving animals.—

- ↑ Cottrell, Chris (February 1, 2013). "German Legislators Vote to Outlaw Bestiality". The New York Times. New York. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ↑ Sweden set to ban bestiality in 2014

- ↑ N.M. Stat. § 30-9A-3

Further reading

- Marie-Christine Anest: Zoophilie, homosexualite, rites de passage et initiation masculine dans la Greece contemporaine (Zoophilia, homosexuality, rites of passage and male initiation in contemporary Greece) (1994), ISBN 2-7384-2146-6

- Dubois-Dessaule: Etude Sur la Bestiality au point de Vue Historique (The Study of Bestiality from the Historical, Medical and Legal Viewpoint) (Paris, 1905)

- Gaston Dubois-Desaulle: Bestiality: An Historical, Medical, Legal, and Literary Study, University Press of the Pacific (November 1, 2003), ISBN 1-4102-0947-4 (Paperback Ed.)

- Hans Hentig Ph.D.: Soziologie der Zoophilen Neigung (Sociology of the Zoophile Preference) (1962)

- Bronisław Malinowski:

The Trobriand Islands (1915)

The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia (1929) - Robson, Bestiality and Bestial Rape in Greek Myth, 1997, S. Deacy and K. F. Pearce (edd.), Rape in Antiquity, Duckworth, 65-96

- Voget, F. W. (1961) Sex life of the American Indians, in Ellis, A. & Abarbanel, A. (Eds.) The Encyclopaedia of Sexual Behavior, Volume 1. London: W. Heinemann, p90-109

- Holy Scriptures-Ezekiel 23:28

- Pages with numeric Bible version references

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 suomi-language sources (fi)

- Articles with French-language sources (fr)

- Articles with Dutch-language sources (nl)

- CS1 Nederlands-language sources (nl)

- Articles with short description

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Articles lacking reliable references from May 2021

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2012

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2017

- Zoo Wiki articles that are excessively detailed from November 2023

- All articles that are excessively detailed

- Wikipedia articles with style issues from November 2023

- All articles with style issues

- Zoophilia

- Zoophilia in culture