Eric Gill: Difference between revisions

meta>Camboxer (addition) |

meta>Jgrantduff |

||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

*Attwater | *{{cite book|last=Attwater|first=Donald|title=A Cell of Good Living|place=London|publisher=G. Chapman|date=1969|isbn=0-225-48865-5}} | ||

*Bringhurst | *{{cite book|last=Bringhurst|first=Robert|title=The Elements of Typographic Style|publisher=Hartley & Marks|date=1992|isbn=0-88179-033-8}} | ||

*Collins | *{{cite book|last=Collins|first=Judith|title=Eric Gill: The Sculpture|place=Woodstock, NY|publisher=Overlook Press|date=1998|isbn=0-87951-830-8}} | ||

*Corey | *{{cite book|last=Corey|first=Steven|last2=MacKenzie|first=Julia (eds)|title=Eric Gill: A Bibliography|publisher=St Paul's Bibliographies|date=1991|isbn=0-906795-53-2}} | ||

*Dodd | *{{cite book|last=Dodd|first=Robin|title=From Gutenberg to OpenType|publisher=Hartley & Marks|date=2006|isbn=0-88179-210-1}} | ||

*Fiedl | *{{cite book|last=Fiedl|first=Frederich|first2=Nicholas|last2=Ott|first3=Bernard|last3=Stein|title=Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Through History|publisher=Black Dog & Leventhal|date=1998|isbn=1-57912-023-7}} | ||

*Fuller Peter | *{{cite book|last=Fuller|first=Peter|title=Essay:Eric Gill,: a Man of Many Parts. Images of God, The Consolations of lost Illusions|publisher=Chatto & Windus|date=1985}} | ||

*Gill | *{{cite book|last=Gill|first=Cecil|first2=Beatrice|last2=Warde|first3=David|last3=Kindersley|title=The Life and Works of Eric Gill|publisher=Papers read at a Clark Library symposium, 22 April 1967|place=Los Angeles|publisher=William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California|date= 1968}} | ||

*Gill | *{{cite book|last=Gill|first=Evan|last2=Peace|first2=David (eds)|title=Eric Gill: The Inscriptions|publisher=Herbert Press|date=1994|isbn=1-871569-66-4}} | ||

*Harling | *{{cite book|last=Harling|first=Robert|title=The letter forms and type designs of Eric Gill|place=Westerham|publisher=Eva Svensson|date=1976|isbn=0-903696-04-5}} | ||

*Holliday | *{{cite book|last=Holliday|first=Peter|title=Eric Gill in Ditchling|publisher=Oak Knoll Press|date=2002|isbn=1-58456-075-4}} | ||

*[[David Kindersley|Kindersley, David]] | *{{cite book|author=[[David Kindersley|Kindersley, David]]|title=Mr. Eric Gill: Further Thoughts by an Apprentice|publisher=Cardozo Kindersley Editions|orig-year=1967|date=1982|isbn=0-9501946-5-4}} | ||

*[[Fiona MacCarthy|MacCarthy, Fiona]] | *{{cite book|author=[[Fiona MacCarthy|MacCarthy, Fiona]]|title=Eric Gill|publisher=Faber & Faber|date=1989|isbn=0-571-14302-4}} | ||

*Macmillan | *{{cite book|last=Macmillan|first=Neil|title=An A–Z of Type Designers|publisher=Yale University Press|date=2006|isbn=0-300-11151-7}} | ||

*Miles | *{{cite book|last=Miles|first=Jonathan|title=Eric Gill & David Jones at Capel-y-ffin|place=Bridgend, Mid Glamorgan|publisher=Seren Books|date=1992|isbn=1-85411-051-9}} | ||

*Pincus | *{{cite book|last=Pincus|first=J.W|first=W.|last=Turner Berry|first2=A. F.|last= Johnson|title=Encyclopædia of Type Faces|publisher=Cassell Paperback|place=London|date=2001|isbn=1-84188-139-2}} | ||

*Skelton | *{{cite book|last=Skelton|first=Christopher (ed.)|title=Eric Gill – The Engravings|place=London|publisher=Herbert|date=1990|date=1-871569-15-X}} | ||

*Speaight | *{{cite book|last=Speaight|first=Robert|title=Life of Eric Gill|place=London|publisher=Methuen|date=1966}} | ||

*Thorp | *{{cite book|last=Thorp|first=Joseph|title=Eric Gill|place=London|publisher=Jonathan Cape|date=1929}} | ||

*Yorke | *{{cite book|last=Yorke|first=Malcolm|title=Eric Gill – Man of Flesh and Spirit|place=London|publisher=Constable|date=1981|isbn=0-09-463740-7}} | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 21:32, 15 June 2015

Eric Gill | |

|---|---|

Eve (1911), engraving by Eric Gill. | |

| Born | Arthur Eric Rowton Gill 22 February 1882 Steyning, Sussex, England |

| Died | 17 November 1940 (aged 58) Middlesex, England |

| Known for | Sculpture, typography |

| Movement | Arts and Crafts movement |

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill (/ˈɡɪl/;[1] 22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, typeface designer, stonecutter and printmaker, who was associated with the Arts and Crafts movement. He is a controversial figure, with his well-known religious views and subject matter generally viewed as being at odds with his sexual behaviour, including his erotic art as well as his sexual abuse of children and of an animal.

Gill was named Royal Designer for Industry, the highest British award for designers, by the Royal Society of Arts. He also became a founder-member of the newly established Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry.

Early life and studies

Gill was born in 1882 in Steyning, Sussex, and grew up in the Brighton suburb of Preston Park.[2] He was the elder brother of MacDonald "Max" Gill (1884–1947), the well known graphic artist. In 1897 the family moved to Chichester. He studied at Chichester Technical and Art School, and in 1900 moved to London to train as an architect with the practice of W.D. Caroe, specialists in ecclesiastical architecture. Frustrated with his training, he took evening classes in stonemasonry at Westminster Technical Institute and in calligraphy at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, where Edward Johnston, creator of the London Underground typeface, became a strong influence. In 1903 he gave up his architectural training to become a calligrapher, letter-cutter and monumental mason.

Career

Sculpture

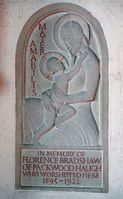

Working from Ditchling in Sussex, where he lived with his wife, in 1910 Gill began direct carving of stone figures. These included Madonna and Child (1910), which Fry described in 1911 as a depiction of 'pathetic animalism', and Ecstasy (1911). Such semi-abstract sculptures showed Gill's appreciation of medieval ecclesiastical statuary, Egyptian, Greek and Indian sculpture, as well as the Post-Impressionism of Cézanne, van Gogh and Gauguin.[3]

His first public success was Mother and Child (1912). A self-described "disciple" of the Ceylonese philosopher and art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy, Gill was fascinated during this period by Indian temple sculpture.[4] Along with his friend and collaborator Jacob Epstein, he planned the construction in the Sussex countryside of a colossal, hand-carved monument in imitation of the large-scale Jain structures at Gwalior Fort in Madhya Pradesh, to which he had been introduced by the Indiaphile William Rothenstein.[5]

In 1914 he produced sculptures for the stations of the cross in Westminster Cathedral. In the same year he met the typographer Stanley Morison. After the war, together with Hilary Pepler and Desmond Chute, Gill founded The Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic at Ditchling, where his pupils included the young David Jones, who soon began a relationship with Gill's daughter, Petra.

Commissioned to produce a war memorial for the University of Leeds, Gill controversially produced a frieze depicting Jesus driving the money-changers from the temple, showing contemporary Leeds merchants as the money-changers (Gill's contention being that the "money men" were a key cause of the war taking place). This is at the Michael Sadler Building at Leeds University.

In 1924 he moved to Capel-y-ffin in Powys, where he set up a new workshop, to be followed by Jones and other disciples. In 1928 he set up a printing press and lettering workshop in Speen. He took on a number of apprentices, including David Kindersley, who in turn became a successful sculptor and engraver, and his nephew, John Skelton, noted as an important letterer and sculptor. Other apprentices included Laurie Cribb, Donald Potter and Walter Ritchie.[6] Others in the household included Denis Tegetmeier, married to Gill's daughter Petra, and Rene Hague, married to the other daughter, Joanna.

In 1928–9, Gill carved three of eight relief sculptures on the theme of winds for Charles Holden's headquarters for the London Electric Railway (now Transport for London) at 55 Broadway, St James's. He carved a statue of the Virgin and Child for the west door of the chapel at Marlborough College.[7]

-

Nude woman naked reclining on a leopard skin, a graphite drawing by Gill (1928)

-

North Wind, 55 Broadway

-

Ariel Between Wisdom and Gaiety, Broadcasting House, 1932

-

Bas relief in Lapworth parish church, 1928

In 1932 Gill produced a group of sculptures, Prospero and Ariel,[8] and others for the BBC's Broadcasting House in London. He was commissioned to produce a sequence of seven bas-relief panels for the facade of The People's Palace, now the Great Hall of Queen Mary University of London, opened in 1936. In 1937, he designed the background of the first George VI definitive stamp series for the Post Office,[9] and in 1938 produced The Creation of Adam, three bas-reliefs in stone for the Palace of Nations, the League of Nations building in Geneva, Switzerland. During this period he was made a Royal Designer for Industry, the highest British award for designers, by the Royal Society of Arts and became a founder-member of the newly established Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry.

His only complete work of architecture was St Peter the Apostle Roman Catholic Church in Gorleston, built in 1938-39.

Midland Hotel, Morecambe

The Art Deco Midland Hotel was built in 1932–33 by the London Midland & Scottish Railway to the design of Oliver Hill and included works by Gill, Marion Dorn and Eric Ravilious.

For the project, Gill produced:

- two seahorses, modelled as Morecambe shrimps, for the outside entrance;

- a round plaster relief on the ceiling of the circular staircase inside the hotel;

- a decorative wall map of the north west of England; and

- a large stone relief of Odysseus being welcomed from the sea by Nausicaa.

Typefaces and inscriptions

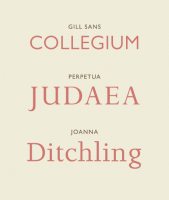

In 1925 he designed the Perpetua typeface, with the uppercase based upon monumental Roman inscriptions, for Morison, who was working for the Monotype Corporation.

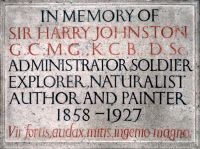

An in-situ example of Gill's design and personal cutting of his Perpetua typeface can be found in the nave of Poling church in West Sussex, on a wall plaque commemorating the life of Sir Harry Johnston. The Perpetua design was followed by the Gill Sans typeface in 1927–30, based on the sans serif lettering originally designed for the London Underground. (Gill had collaborated with Edward Johnston in the early design of the Underground typeface, but dropped out of the project before it was completed.) In the period 1930–31 Gill designed the typeface Joanna which he used to hand-set his book, An Essay on Typography.

-

Specimens of typefaces by Eric Gill

-

Sir Harry Johnston memorial plaque

Eric Gill's types include:

- Gill Sans (his most famous face and lasting legacy to typography 1927–30)

- Perpetua (1926)

- Perpetua Greek (1929)[10]

- Golden Cockerel Press Type (for the Golden Cockerel Press; 1929)

- Solus (1929),

- Joanna (based on work by Granjon; 1930–31)

- Aries (1932)

- Floriated Capitals (1932)

- Bunyan (1934)

- Pilgrim (recut version of Bunyan; 1953)

- Jubilee (also known as Cunard; 1934)

In his 1947–49 redesign for Penguin Books, a project that resulted in the establishment of Penguin Composition Rules, Jan Tschichold specified use of Gill Sans for book titles, and in branding their Pelican imprint. In the 1990s, the BBC adopted Gill Sans for its wordmark and many of its on-screen television graphics.

Published writings

He published numerous essays on the relationship between art and religion. He also produced a number of erotic engravings.[11]

Some of his writings include:

- A Holy Tradition of Working: An Anthology of Writings[12]

- Clothes: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women[13]

- An Essay on Typography[14]

- Christianity and Art, 1927

- Art, 1934

- Work and Property, 1937[15]

- Work and Culture, 1938

- Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus[16]

- Notes on Postage Stamps[17]

Political views

As a young man, Gill had been a member of the Fabian Society, but later resigned.[18]

In the 1930s Gill became a supporter of social credit; later he moved towards a socialist position.[19] In 1934, Gill contributed art to an exhibition mounted by the left-wing Artists' International Association, and defended the exhibition against accusations in The Catholic Herald that its art was "anti-Christian".[20] Gill was adamantly opposed to fascism, and was one of the few Catholics in Britain to openly support the Spanish Republicans.[19] Gill also became a pacifist, and helped set up the Catholic peace organisation Pax with E. I. Watkin and Donald Attwater.[21] Later Gill joined the Peace Pledge Union, as well as supporting the British branch of the Fellowship of Reconciliation.[19]

Personal life

In 1904 he married Ethel Hester Moore (1878–1961), with whom he had three daughters and an adopted son. In 1907 he moved with his family to "Sopers", a house in the village of Ditchling in Sussex, which would later become the centre of an artists' community inspired by Gill.

In 1913 he moved to Hopkin's Crank at Ditchling Common, two miles north of the village. In 1924 he moved to Capel-y-ffin in Wales. Gill soon tired of Capel-y-ffin, coming to feel that it had the wrong atmosphere and was too far from London, where most of his clients were. In 1928 he moved to Pigotts at Speen near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire,[22]

He was a deeply religious man, largely following the Roman Catholic faith, but his beliefs and practices were by no means orthodox.[23] His personal diaries describe his sexual activity in great detail including the claim that he sexually abused his two eldest daughters, had incestuous relationships with his sisters and performed sexual acts on his dog.[23] This aspect of Gill's life was little known until publication of the 1989 biography by Fiona MacCarthy. The 1966 biography by Robert Speaight mentioned none of it.

Gill died of lung cancer in Harefield Hospital in Middlesex in 1940. He was buried in Speen churchyard in the Chilterns, near Princes Risborough, the village where his last artistic community had practised. His papers and library are archived at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library at UCLA.[24]

Contribution

As the revelations about Gill's private life reverberated, there was a reassessment of his personal and artistic achievement. As his recent biographer sums up:

After the initial shock, [...] as Gill's history of adulteries, incest, and experimental connection with his dog became public knowledge in the late 1980s, the consequent reassessment of his life and art left his artistic reputation strengthened. Gill emerged as one of the twentieth century's strangest and most original controversialists, a sometimes infuriating, always arresting spokesman for man's continuing need of God in an increasingly materialistic civilization, and for intellectual vigour in an age of encroaching triviality.[25]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Olausson, Lena; Sangster, Catherine (2006). Oxford BBC Guide to Pronunciation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-19-280710-6.

- ↑ Findmypast.co.uk

- ↑ "Eric Gill - Tate". Tate. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ Video of a Lecture at London University detailing Gill's interest in Indian Sculpture, London University School of Advanced Study, March 2012.

- ↑ Arrowsmith, Rupert Richard (2010). Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African, and Pacific Art and the London Avant-Garde. Oxford University Press. pp. 74–103. ISBN 978-0-19-959369-9.

- ↑ C.f. Donald Potter, My Time with Eric Gill: A Memoir, Gamecock Press, 1980, ISBN 0-9506205-1-3.

- ↑ "Art & Architecture". marlboroughcollege.org. 20 July 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ Illustration.

- ↑ Peter Worsfold, Great Britain King George VI Low Value Definitive Stamps, The Great Britain Philatelic Society, 2001, ISBN 0-907630-17-0. The effigy of George VI was drawn by Edmund Dulac, who has a passionate epistolary debate with Gill in newspapers about stamp designing after the Edward VIII postage stamps late 1936, quoted in Colin White, Edmund Dulac, Studio Vista, 1977, p. 172.

- ↑ Harling, Robert (1978). The Letter Forms and Type Designs of Eric Gill. Boston, MA: Eva Svensson and David R. Godine. ISBN 0-87923-200-5.

- ↑ Christopher Skelton (ed.), Eric Gill, The Engravings, Herbert Press, 1990, ISBN 1-871569-15-X.

- ↑ Gill, Eric. (1983). A Holy Tradition of Working: An Anthology of Writings Golgonooza Press. ISBN 0-903880-30-X.

- ↑ Cape, Jonathan. (1931). Jonathan Cape. Gill contributed: Clothes: An Essay Upon the Nature and Significance of the Natural and Artificial Integuments Worn by Men and Women

- ↑ Gill, Eric. (1931). An Essay on Typography ISBN 0-87923-762-7, ISBN 0-87923-950-6 (reprints).

- ↑ Gill, Eric. (1937). Trousers & The Most Precious Ornament. London: Faber and Faber. oclc 5034115

- ↑ Jonathan Cape, 1940 (published posthumously) Autobiography: Quod Ore Sumpsimus. ISBN 1-870495-13-6

- ↑ Gill, Eric. (2011). Notes on Postage Stamps Kat Ran Press, 2011. ISBN 0-9794342-1-1.

- ↑ Britian, Ian (1982). Fabianism and culture: a study in British socialism and the arts c.1884–1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7, 12. ISBN 0-521-23563-4.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Ceadel, Martin (1980). Pacifism in Britain, 1914–1945: The Defining of a Faith. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 281, 289–91, 295, 321. ISBN 0-19-821882-6.

- ↑ Harrison, Charles (1981). English Art and Modernism 1900–1939. London: Allen Lane. pp. 251–2. ISBN 0-253-13722-5.

- ↑ Coy, Patrick G. (1988). A Revolution of the Heart: Essays on the Catholic Worker. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-87722-531-1.

- ↑ Font Designer – Eric Gill Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 McCarthy, Fiona (17 October 2009). "Mad about sex." The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ↑ Aid for the Collection on Eric Gill, 1887–2003.

- ↑ MacCarthy, Fiona (2004). "Gill, (Arthur) Eric Rowton (1882–1940)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

Bibliography

- Attwater, Donald (1969). A Cell of Good Living. London: G. Chapman. ISBN 0-225-48865-5.

- Bringhurst, Robert (1992). The Elements of Typographic Style. Hartley & Marks. ISBN 0-88179-033-8.

- Collins, Judith (1998). Eric Gill: The Sculpture. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-830-8.

- Corey, Julia (eds); MacKenzie (1991). Eric Gill: A Bibliography. St Paul's Bibliographies. ISBN 0-906795-53-2.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Dodd, Robin (2006). From Gutenberg to OpenType. Hartley & Marks. ISBN 0-88179-210-1.

- Fiedl, Frederich; Ott, Nicholas; Stein, Bernard (1998). Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Through History. Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 1-57912-023-7.

- Fuller, Peter (1985). Essay:Eric Gill,: a Man of Many Parts. Images of God, The Consolations of lost Illusions. Chatto & Windus.

- Gill, Cecil; Warde, Beatrice; Kindersley, David (1968). The Life and Works of Eric Gill. Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California.

- Gill, Evan; Peace, David (eds) (1994). Eric Gill: The Inscriptions. Herbert Press. ISBN 1-871569-66-4.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Harling, Robert (1976). The letter forms and type designs of Eric Gill. Westerham: Eva Svensson. ISBN 0-903696-04-5.

- Holliday, Peter (2002). Eric Gill in Ditchling. Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 1-58456-075-4.

- Kindersley, David (1982) [1967]. Mr. Eric Gill: Further Thoughts by an Apprentice. Cardozo Kindersley Editions. ISBN 0-9501946-5-4.

- MacCarthy, Fiona (1989). Eric Gill. Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-14302-4.

- Macmillan, Neil (2006). An A–Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11151-7.

- Miles, Jonathan (1992). Eric Gill & David Jones at Capel-y-ffin. Bridgend, Mid Glamorgan: Seren Books. ISBN 1-85411-051-9.

- Johnson, W. (2001). Encyclopædia of Type Faces. London: Cassell Paperback. ISBN 1-84188-139-2.

{{cite book}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help) - Skelton, Christopher (ed.) (1-871569-15-X). Eric Gill – The Engravings. London: Herbert.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Speaight, Robert (1966). Life of Eric Gill. London: Methuen.

- Thorp, Joseph (1929). Eric Gill. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Yorke, Malcolm (1981). Eric Gill – Man of Flesh and Spirit. London: Constable. ISBN 0-09-463740-7.

External links

- The Eric Gill Society.

- Portraits by Eric Gill at the National Portrait Gallery.

- Portraits of Eric Gill at the National Portrait Gallery.

- Eric Gill in the Crafts Study Centre.

- Eric Gill in the Central Saint Martins Museum and Study Collection.

- Eric Gill (1882–1940) at Identifont

- "Written in stone", article on Gill's private life in relation to his work by Fiona MacCarthy

- "Baptism by fire", MacCarthy article on her discovery and publication of the details of Gill's sexual activity

- "Can the art of a paedophile be celebrated?". BBC News. 5 September 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2008., article on the relationship of Gill's sexual deviance to his art, By Finlo Rohrer, BBC News Magazine.

- "Looking for Mr Gill" BBC Storyville Documentary on Eric Gill; filmed and directed by Luke Holland

- Postage stamps designed by Eric Gill

- Eric Gill Article on The National Archives website which deals with many of Gill's works

- London Transport Museum Photographic Archive

- "An Essay on Typography" PDF copy of the book by Eric Gill

- 3D model of Gill's 1910-1 Ecstasy via photogrammetric survey

Lua error in Module:Authority_control at line 1170: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value).

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- EngvarB from August 2014

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Use dmy dates from August 2014

- Articles with hCards

- Pages using infobox artist with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 errors: generic name

- CS1 errors: missing name

- CS1 errors: dates

- Commons category link from Wikidata

- 1882 births

- 1940 deaths

- British architectural sculptors

- English sculptors

- English graphic designers

- English illustrators

- English wood engravers

- People from Brighton

- People from Ditchling

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- English Roman Catholics

- English typographers

- Communication design

- Stamp designers

- English pacifists

- English anti-fascists

- English socialists

- Alumni of the Central School of Art and Design

- Arts and Crafts Movement

- Monumental masons

- Stone carvers

- British letter cutters

- Burials in Berkshire

- Academics of the Central School of Art and Design

- English sex offenders

- Child sexual abuse

- Zoophilia